Improving Diversity in Clinical Trial Volunteer Participation by Addressing Racial and Ethnic Representation Among the Clinical Research Workforce

2020 Tufts CSDD study examines relationship between investigative site personnel diversity and study participant diversity.

Although we have witnessed increased inclusion of diverse populations in COVID-19 vaccine1 and treatment2 trials over the past two years, in nearly all other disease indications, representation of BIPOC3 populations—black, indigenous, and peoples of color—in clinical trials remains comparatively low, particularly in world regions where most clinical trials are currently conducted4 and where demographics are becoming increasingly more diverse (i.e., North America and Western Europe).

A variety of factors help explain the lack of racial and ethnic representation among clinical trial volunteer participants. Low clinical research literacy, poorly targeted communications, and limited access to clinical research facilities are among top factors mentioned.5 Many note that racial and ethnic representation among the research workforce is essential in reducing barriers to clinical study volunteer participation among historically underrepresented populations.6 A 2008 study conducted by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (Tufts CSDD) found that a physician’s race and ethnicity can influence the race and ethnicity of clinical trial volunteers. The study also found that incidence of participation in clinical research among BIPOC physicians was well below that observed among white physicians. Although interest in becoming a clinical investigator was high among all physicians surveyed, BIPOC investigators tended to conduct and initiate fewer trials annually. In that study, BIPOC investigators also reported fewer infrastructural resources and support compared to white investigators.

More than a decade has passed since the 2008 study. During that time, public and clinical research stakeholder awareness and interest in improving the proportional representation of volunteer participants by race and ethnicity in clinical trials has intensified. Several recent initiatives underscore these changes. The FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017, for example, expanded the FDA’s authority to address barriers to participation in clinical trials (SEC.610.Expanded Access).7 In 2020, FDA issued guidance for the broadening of volunteer eligibility criteria and the enhancement of diversity in clinical trial participation.8 In April 2022, FDA issued draft guidance recommending the development and submission of plans—with each new IND application—for achieving diversity targets, as well as retaining study participants.9 Separately, The Lancet issued a diversity pledge to reinforce its commitment to diversity10 and the New England Journal of Medicine conveyed the importance of diversity in clinical research in a recent editorial.11

In late 2020, Tufts CSDD conducted a new study to revisit, characterize, and more deeply examine the relationship between investigative site personnel diversity and study participant diversity.

This research began with the formation of a large Working Group12 of biopharmaceutical companies, contract research organizations (CROs), and one global professional association. The Working Group supported the development of two extensive online global surveys that were distributed between April and July of 2021. These were reviewed and approved by the Tufts University IRB and the university’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) expert reviewer.

The first survey targeted medical professionals, regardless of their involvement in the clinical research process. Its purpose was to gather data about medical professionals regarding their awareness of, access to, training, and involvement in clinical research. The second survey targeted clinical research professionals working at various types of clinical research sites. Its purpose was to gather data on staff diversity at investigative sites, the infrastructure and support available to clinical research staff, and staff perceptions about Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI).

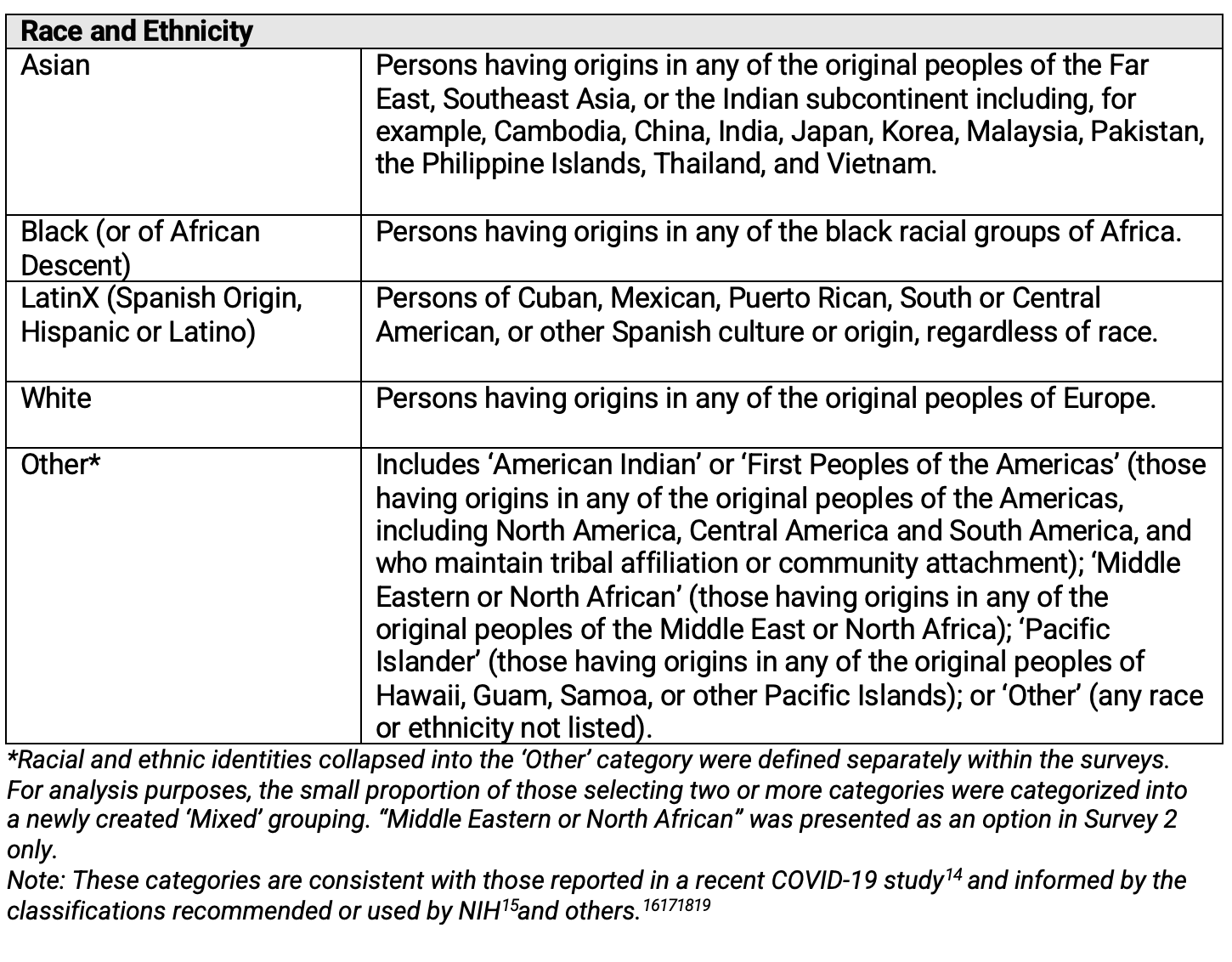

Definitions of race and ethnicity were presented to respondents participating in both surveys as shown in Table 1. These definitions are consistent with those reported in a 2021 study looking at race and ethnicity of COVID-19 patients participating in 68 studies worldwide.13

Table 1. Race and Ethnicity—Definitions Presented to Respondents

Survey one: Awareness of, access to, training in, and involvement in clinical research among medical and allied health professionals

In total, 611 respondents participated in the online survey aimed at medical professionals regardless of their involvement in clinical research. Of these, 54% were in North America (US & Canada) and 46% were in Rest of World (ROW). Regarding their education levels, 62% had a doctoral or medical degree, 24% had a nursing degree, and 14% had achieved other educational levels, such as a bachelors or high school diploma. Respondents to the survey were 56% female and 44% male. Racial and ethnic identities were reported as follows: 68% White, 15% Asian, 10% Other (including mixed race/ethnicity), 4% LatinX, and 3% Black.

The survey results show that most medical and allied health professionals who are involved in clinical research believe that mentors made them more comfortable with (1) the clinical trial process (93%), and (2) referring and screening patients for clinical trials (91%). Most medical and allied health professionals involved in clinical research (87%) also believe that mentors helped them find greater access to clinical trials.

The survey findings also indicate that a high proportion of medical and allied health professionals first became exposed to clinical research at the invitation of a peer or mentor. Differences in exposure through a mentor or peer were also observed between BIPOC and white professionals, with 42% of white professionals reporting becoming involved in clinical research in this manner compared to only 30% of BIPOC professionals. Other differences in exposure among BIPOC and white professionals were found when respondents were asked if they first became exposed to clinical research by proactively contacting a pharmaceutical company about opportunities to participate as staff supporting or leading clinical trials. Thirteen percent of BIPOC professionals reported becoming involved in clinical trials by being proactive compared to 6% of white professionals.

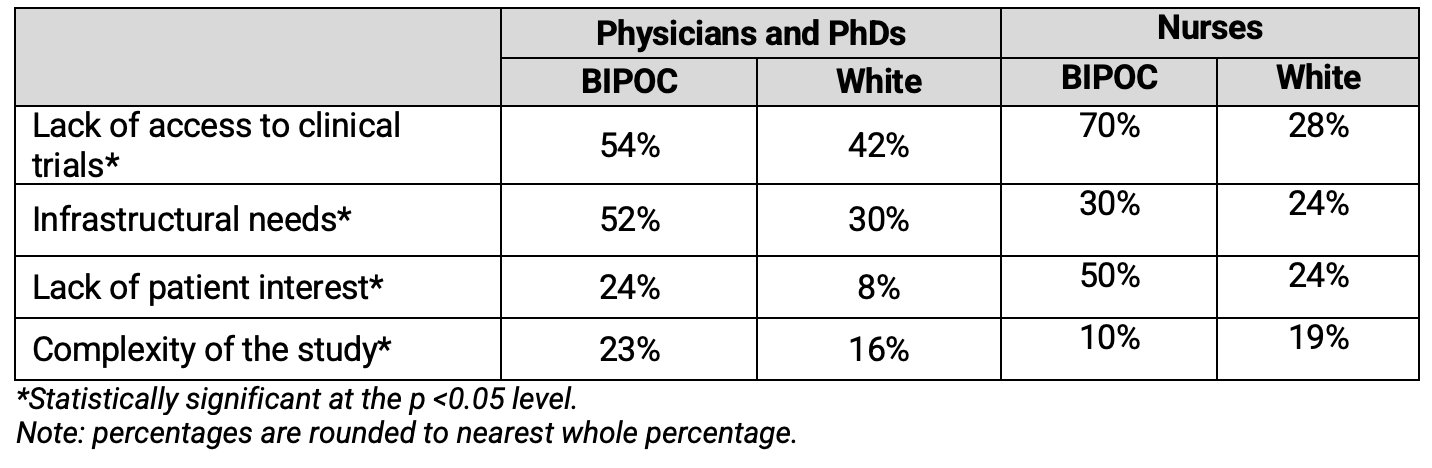

Further, differences in access to clinical research opportunities and infrastructure were identified between BIPOC and white medical and allied health professionals who have not been involved in clinical trials. Table 2 shows the barriers to involvement in clinical trials as reported by Physicians, PhDs and nurses who have not been involved in clinical research worldwide.

Table 2. Barriers to Involvement in Clinical Research as Reported by Professionals Without Clinical Trial Experience (Global)

Survey two: Investigative site diversity, infrastructure, and support available to clinical research site staff

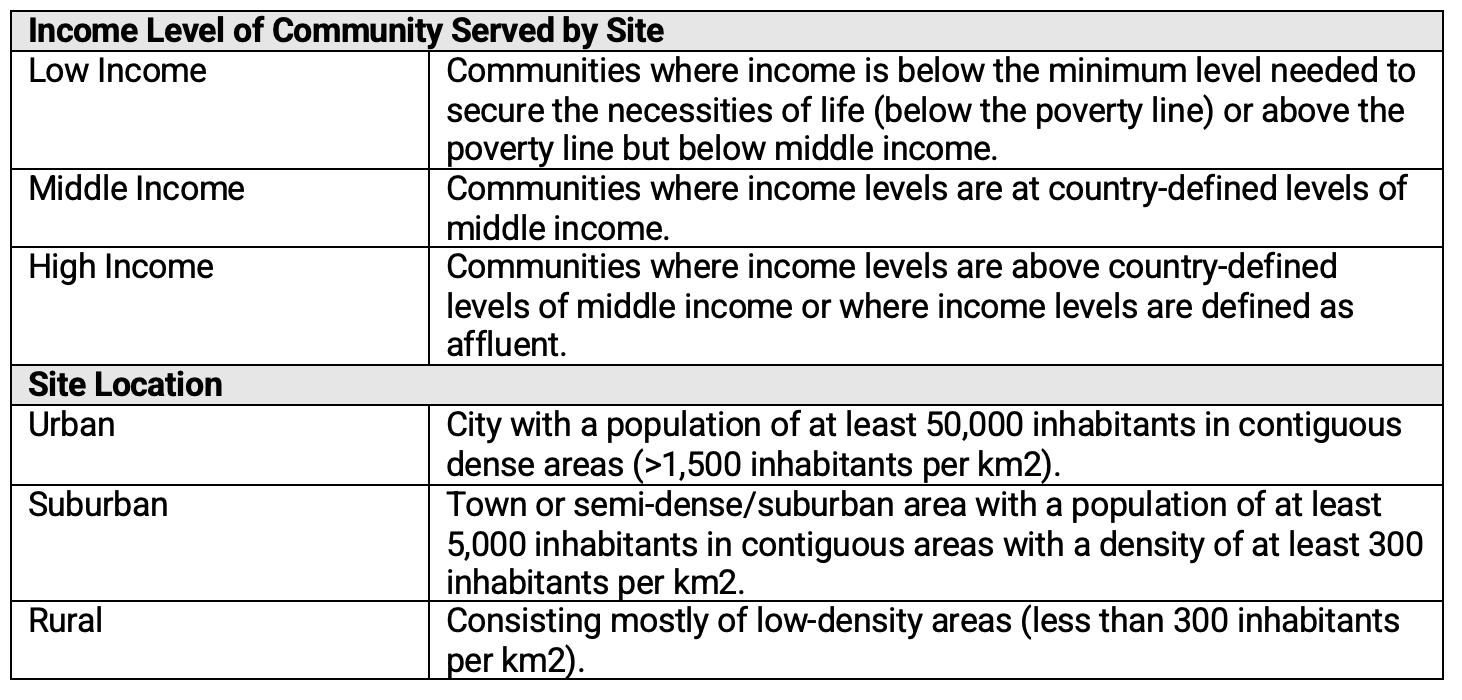

The primary aim of the second survey was to understand current racial and ethnic representation among research professionals at clinical research sites supporting clinical trials funded by pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, and the elements that influence staff diversity at these sites. These elements include (1) the types of communities served (i.e., urban, suburban, and rural), (2) the income levels of the patient population served, (3) staff’s access to technologies, (4) training and support available to site staff, and (5) the site’s infrastructure. To that end, in addition to the definitions shown in Table 1, respondents to this survey were also provided with the definitions included in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Site Characteristics—Subgroup Definitions

In total, 3,462 respondents—representing an estimated 3,34020 unique sites—participated in this global21 online survey. Of these respondents, 40% were principal investigators, 36% were site directors and managers and other administrative staff, and 25% were clinical research coordinators (CRCs) or clinical research nurses. Respondents to this survey were 61% female and 39% male. Racial and ethnic identities were reported as follows: 69% White, 12% LatinX, 8% Asian, 6% Mixed, 4% Black, and 2% Other.

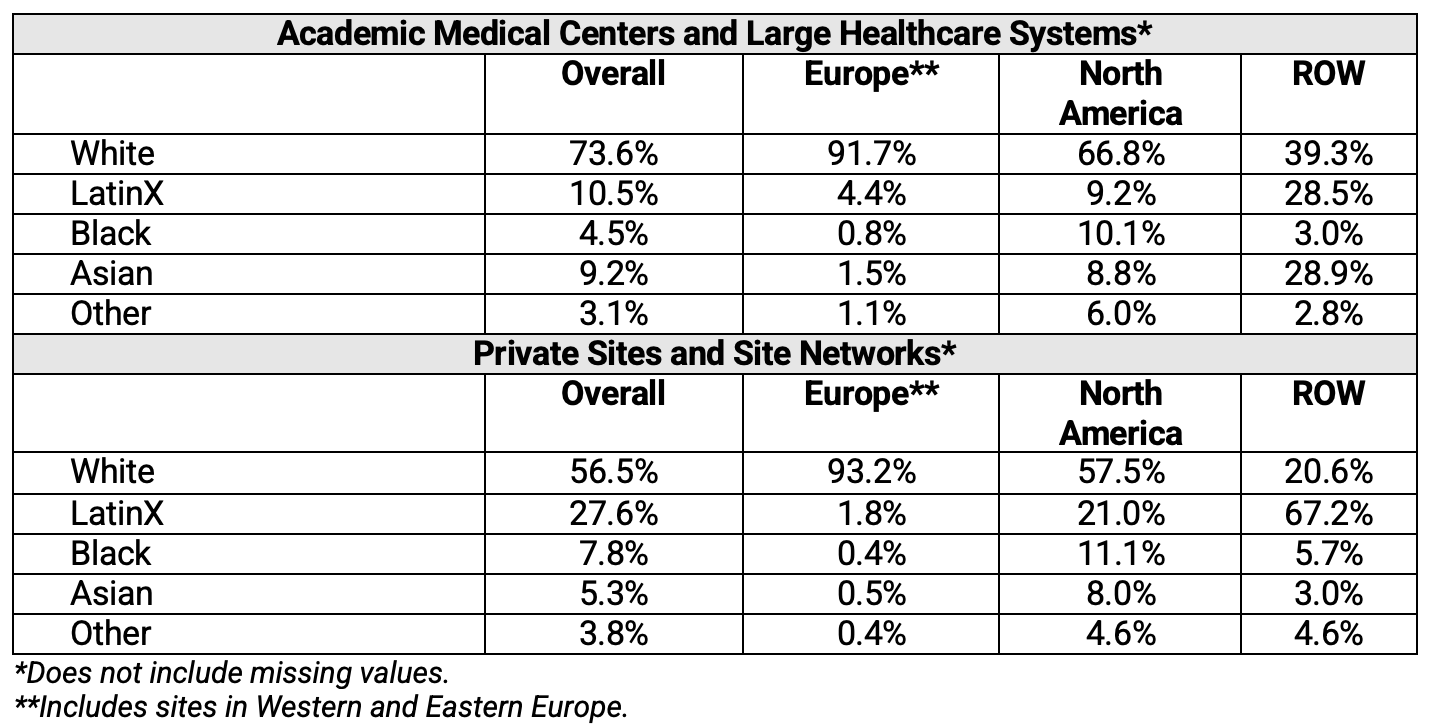

In addition, survey respondents were asked to estimate the racial and ethnic breakdown/composition of the staff working at their respective sites. Table 4 shows this breakdown by world region and type of research institution. Overall, BIPOC populations were not widely represented among staff at clinical research sites globally. When comparing BIPOC percentage representation by type of institution in North America, higher representation was observed in private sites and site networks compared to academic medical centers and large healthcare systems. When comparing BIPOC percentage representation by type of institution in Europe, significant differences in representation were not observed among private sites, site networks, academic medical centers, and large healthcare systems. BIPOC representation was higher among staff at research sites located in ROW.

Table 4. Distribution of Investigative Site Staff by Race and Ethnicity

Clinical research sites were also classified into one of two groupings: ‘High’ Staff Diversity Sites and ‘Low’ Staff Diversity Sites. Sites in the US were classified as High Staff Diversity if their staff was at least 60% BIPOC. Sites in the US were classified as Low Staff Diversity if their staff was 40% or less BIPOC. Sites in locations outside of the US were classified as High Staff Diversity Sites if representation by any one race or ethnicity was 40% or lower; they were classified as Low Staff Diversity Sites if representation by one race or ethnicity was 60% or higher. Sites that fell outside of these parameters (i.e., the 50th percentile) were excluded from supplementary analyses. It is important to note that less than 1% of European sites met the criteria for the High Staff Diversity grouping—this includes sites in Eastern Europe as well as the UK, Germany, Spain, France, and other parts of Western Europe.

Clinical trial volunteer diversity is strongly associated with diversity in the clinical research workforce

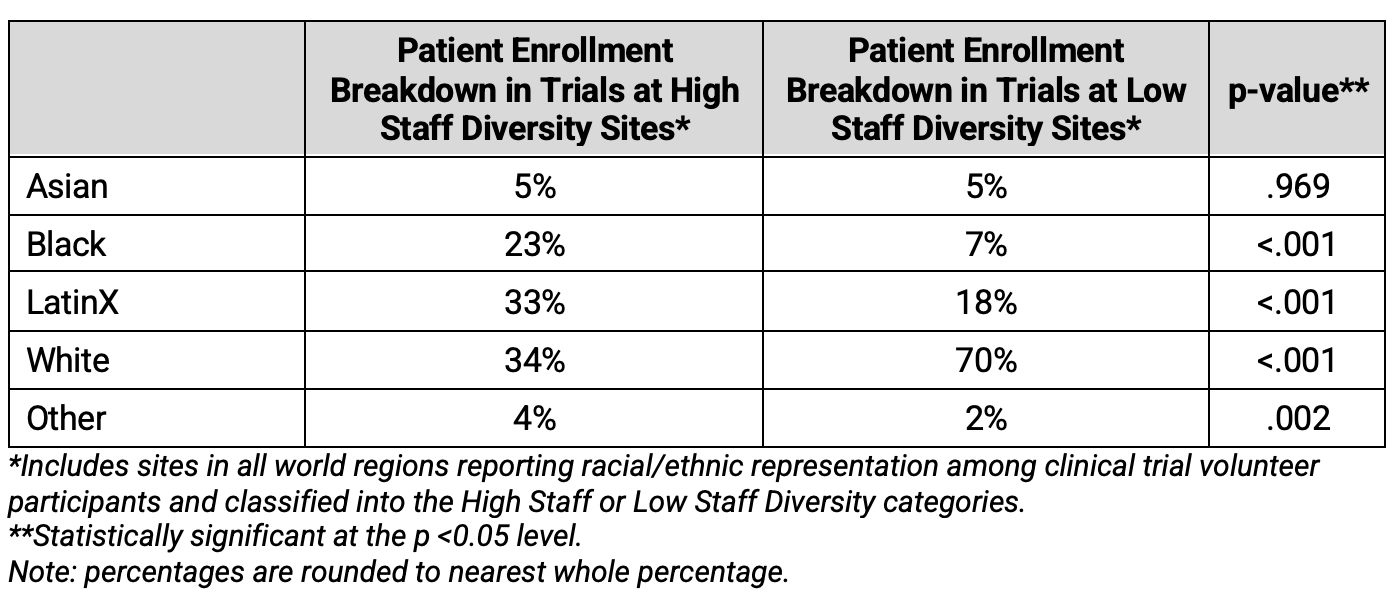

Racial and ethnic representation among the clinical research site workforce is associated with racial and ethnic representation in clinical trial volunteer enrollment. To explore the strength of this relationship, respondents were asked to estimate the racial and ethnic breakdown of patients enrolled in their recently conducted clinical trials. These estimates were then cross tabulated against the groupings for High Staff Diversity Sites and Low Staff Diversity Sites, and chi-square tests were conducted to determine statistical significance. As shown in Table 5, the enrollment of BIPOC patients was significantly higher at High Staff Diversity Sites, including all site types. This result was statistically significant.

Table 5. Relationship Between Staff Diversity in Diversity in Patient Enrollment in Trials (Global)

The relationship between diversity in patient enrollment and investigative site staff diversity has important implications for the development of DEI plans and policies. If the aim is to increase representation among clinical trial volunteers, policies and plans must also prioritize improvements in representation of BIPOC populations among investigative site staff; thus, understanding the basic characteristics of sites that show High Staff Diversity is a meaningful starting point for future initiatives in this space.

Characteristics of investigative sites reporting higher staff diversity

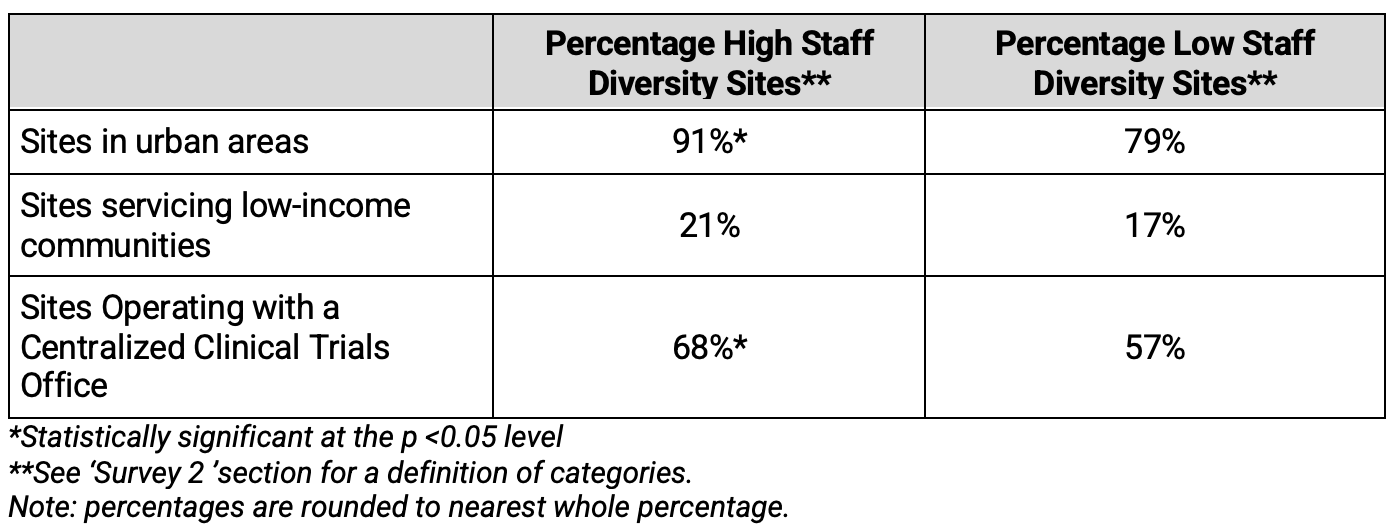

This study sheds light on the characteristics of sites reporting higher levels of staff diversity—though it also uncovers barriers faced by those sites reporting lower levels of staff diversity. Sites reporting higher racial and ethnic diversity among their staff tended to be in urban areas, service low-income communities, and have centralized clinical trials offices to support research teams—in greater proportion than sites reporting lower staff diversity levels. As shown in Table 6, two of these findings were statistically significant.

Table 6. General Characteristics of Investigative Site Staff by Diversity Subgroup

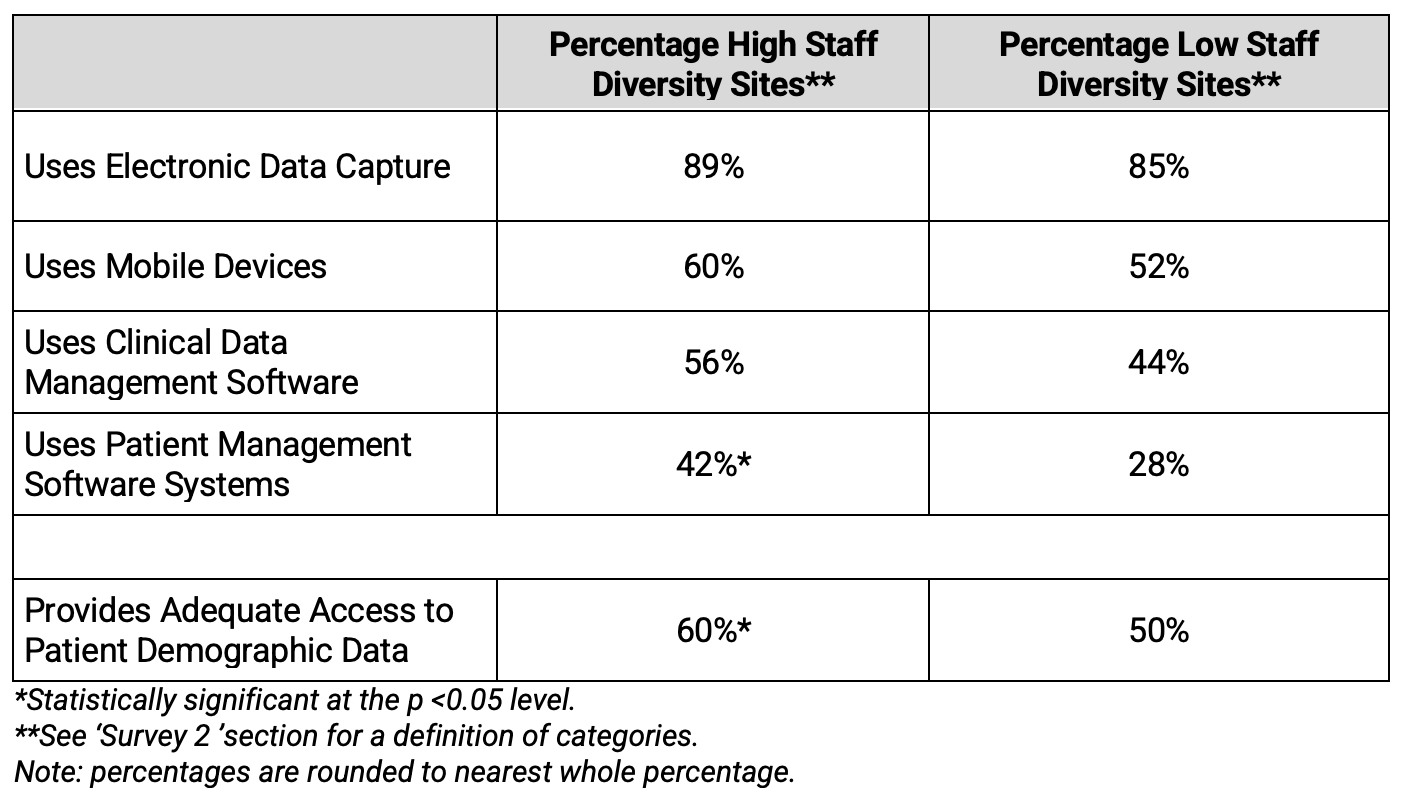

Clinical research sites reporting High Staff Diversity levels also reported greater use of technologies and infrastructure to support the execution of clinical research compared to Low Staff Diversity sites, as shown in Table 7. The difference in use of Patient Management Systems at High Staff diversity sites compared to Low Staff Diversity sites was statistically significant. Additionally, provision of adequate access to Patient Management Data was higher at High Staff Diversity sites. The analysis also revealed that, prior to the pandemic, remote communication platforms were used in higher proportion at High Staff Diversity sites compared to Low Staff Diversity sites, and that the overall current use of these platforms was higher at High Staff Diversity sites.

Table 6. Use of Technology and Infrastructure by Diversity of Investigative Site Staff

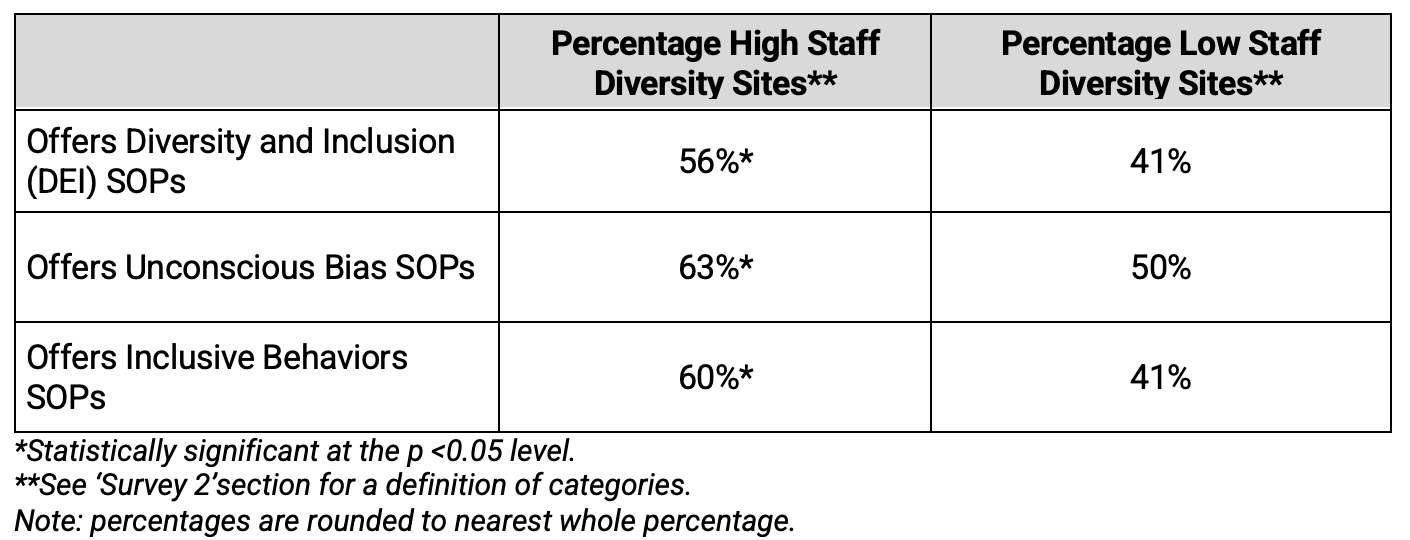

Not least, this research revealed that High Staff Diversity Sites tended to offer better access to diversity and inclusion, unconscious bias, and inclusive behavior SOPs to its staff. The offering of inclusive behavior SOPs was notably higher at High Staff Diversity sites.

Table 7. Presence of Diversity SOPs by Diversity of Investigative Site Staff

Conclusions

The Tufts CSDD Investigative Site Personnel Diversity Study results demonstrate association between reported levels of racial and ethnic diversity among personnel at investigative sites and racial and ethnic representation among volunteer participants enrolled in clinical trials. This finding suggests that increased diversity within the clinical research workforce facilitates the racial and ethnic representation of study volunteers in clinical trials at individual research sites.

This study also offers new understanding about shared characteristics among sites reporting comparatively higher staff diversity and offers insight into the paths followed by medical and allied health professionals toward becoming involved in clinical trials. These elements are key considerations and may be important strategies supporting improvements in racial and ethnic representation among clinical trial volunteers.

Specifically, our results suggest that expanding exposure to clinical research opportunities to all medical and allied health professionals can lead to greater overall staff participation in clinical investigation. Our results show that 87% of all professionals involved in clinical research believe that mentors helped them find greater access to clinical trials, and over 90% of all medical and allied health professionals involved in clinical research report that a mentor made them feel more comfortable with the clinical trial process, as well as in referring and screening patients for trials. However, only 30% of BIPOC medical and allied health professionals first became involved in clinical research by invitation by a mentor or peer compared to 42% among their white counterparts. This last result highlights a disparity in access to mentors in clinical research and the benefits that accompany such connections. Mentorship and other research socialization programs are therefore expected to be effective in increasing overall and BIPOC staff participation in clinical research.

The study findings indicate that the presence of DEI-specific materials and SOPs may play a role in supporting workforce diversity and, in turn, foster diversity and inclusion among study volunteers. First, a strong relationship was identified between High Staff Diversity sites and the availability and use of Diversity and Inclusion, Unconscious Bias, and Inclusive Behaviors SOPs. Second, High Staff Diversity Sites reported access to these SOPs in higher proportion compared to Low Staff Diversity sites. Third, approximately half of staff at clinical research sites—across site types and locations—believe that SOPs for Diversity & Inclusion, Unconscious Bias, and Inclusive Behaviors help increase participant diversity at sites. Our results set the stage for drug development stakeholders to collaborate in the development and dissemination of materials, policies and procedures that elevate awareness and understanding of the importance of inclusive behaviors and minimizing biases. This collaboration is not just isolated to the level of the investigator site, but also can benefit from involvement of sponsoring organizations and CROs to support such efforts to increase DEI awareness.

Altogether, our research demonstrates that a diverse clinical research workforce is associated with diversity among clinical trial volunteers, shows that diversity in the clinical research workforce still falls short of reflecting the diversity of the global patient population, and identifies key areas that can support increased racial and ethnic representation among site staff: offering mentorship in clinical research to medical and allied health professionals, as well as SOPs and educational materials related to diversity and inclusion, unconscious bias, and inclusive behaviors.

Maria I. Florez, MA, Research Consultant and Senior Analyst, Tufts CSDD, Tufts University School of Medicine, Emily Botto, BA, Research Analyst, Tufts CSDD, Tufts University School of Medicine, Zoma Foster, PhD, Strategic Feasibility Manager, UCB, Earl Seltzer, Senior Director, Global Feasibility, Labcorp Drug Development Inc., Barbara Valastro, PhD, Senior Director Patient Insights and Solutions, Portfolio Transformation and Insights, Biopharmaceuticals R&D, AstraZeneca, Gothenburg, Sweden, Linda Ashmore, Director Oncology Hematology, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Kenneth Getz, MBA, Executive Director and Professor, Tufts CSDD, Tufts University School of Medicine

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Zachary Smith for his contributions. The authors also thank representatives from the following organizations for providing research grants and support to this study: AbbVie, Amgen, Association of Clinical Research Professionals, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Covance (now Labcorp Drug Development), CSL Behring, Eli Lilly and Company, EMD Serono, ICON, IQVIA, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Parexel, Pfizer, Sanofi, Seagen, Syneos Health, Takeda, UCB, and Genentech, a member of the Roche group. Additionally, the authors wish to thank the following for their assistance: Philippine Nurses Association of America, Asian American Pacific Islander Nurses Association, Taiwan Clinical Research Association, Academy of Physicians in Clinical Research, European Society for Clinical Investigation, ARMA UK, ARCS Australia, Hong Kong Medical Association, the Israeli Medical Association, and the Society of Clinical Research Sites.

References

- Artiga S, et. al. Racial Diversity within COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Trials: Key Questions and Answers. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021.

- Stewart J, Krows ML, Schaafsma TT, et al. Comparison of Racial, Ethnic, and Geographic Location Diversity of Participants Enrolled in Clinic-Based vs 2 Remote COVID-19 Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148325. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48325

- An article published by the New York Times states that the earliest use of the term BIPOC was in 2013. The acronym stands for black, indigenous, and peoples of color.https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-bipoc.html

- Getz K, Smith Z, Pena Y.Quantifying Patient Subgroup Disparities in New Drugs and Biologics Approved Between 2007 - 2017. TIRS (2020); 54(6): 1541-1550.

- Bierer B, White S, Maloney L, Ahmed H, Strauss D, Clark L.Achieving Diversity, Inclusion and Equity in Clinical Research.(2020). https://mrctcenter.org/blog/resources/achieving-diversity-inclusion-and-equity-in-clinical-trials-principles

- Holden L and Richardson LD. Disparities and Diversity in Biomedical Research. Chapter 18. Diversity and Inclusion in Quality Patient Care (Martin et al). Springer International Publishing. Switzerland. (2016)

- https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ52/PLAW-115publ52.pdf

- https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/enhancing-diversity-clinical-trial-populations-eligibility-criteria-enrollment-practices-and-trial

- https://www.fda.gov/media/157635/download

- https://www.thelancet.com/diversity

- Editorial. Striving for Diversity in Research Studies. N Engl J Med 385; 15. October 7, 2021.

- The Tufts CSDD Investigative Site Personnel Study Working Group included the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP), five contract research organizations (Covance—now Labcorp Drug Development, ICON, IQVIA, Parexel, Syneos Health) and 17 biopharmaceutical companies (AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly and Company, EMD Serono, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Sanofi, Seagen, Takeda, UCB, and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group).

- Magesh S, John D, Wei, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status, November 11, 2021. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(11):e2134147. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147 (Reprinted)

- Magesh S, John D, Wei, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status, November 11, 2021. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(11):e2134147. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147 (Reprinted)

- Racial and Ethnic Categories and Definitions for NIH Diversity Programs and for Other Reporting Purposes. April 8, 2015. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 1 March 2022 from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not-od-15-089.html.

- United Nations Ethnocultural Characteristics. United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved 1 March 2022 from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sconcerns/popchar/popchar2.htm.

- Cunningham, W, Jacobsen, J. Earnings Inequality Within and Across Gender, Racial, and Ethnic Groups in Four Latin American Countries. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. April 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2022 from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/6724/wps4591.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Jensen, E, Jones, N, Orozco, K, Medina, L, Perry, M, et al. Measuring Racial and Ethnic Diversity for the 2020 Census. August 4, 2021. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 1 March 2022 from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2021/08/measuring-racial-ethnic-diversity-2020-census.html

- Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. August 28, 1995. Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Retrieved 1 March 2022 from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_race-ethnicity.

- This estimate is based on an analysis of 12 unique variables included in the dataset and on the application of a 3.4% duplication rate. The number of sites represented here accounts for approximately 40% of the total number of unique investigative sites involved in FDA-regulated clinical trials in 2020.

- Sixty-two countries were represented. Fifty percent of sites were in the US and Canada, thirty-two percent were in Europe, ten percent were in Central and South America (including Mexico), four percent were in Asia and Pacific, and four percent were in ROW (rest of world).

Patient and Site Personnel Perceptions of Retail Pharmacy Involvement in Clinical Research

March 7th 2024Despite industry-wide excitement over the involvement of retail pharmacies in clinical research, there is little information currently available on how retail pharmacies are perceived by investigative sites and patients.