Pharmaceutical Industry and Pediatric Clinical Trial Networks in Europe – How Do They Communicate?

Pair of surveys provide a rare formal peek into the relationship between sponsors and pediatric clinical research networks. A lack of awareness, incongruent expectations, and insufficient communication have hindered collaboration between the two parties. Developing standardized procedures and better information exchange could help strengthen the connection going forward.

Recent legislation and regulatory initiatives, first in the U.S. with the Pediatric Rule and later with the Best Pharmaceutical for Children Act and the Pediatric Research Equity Act, and later in Europe with the Pediatric Regulation in 20071,2,3 required the pharmaceutical industry to conduct high quality research in the development of medicines for children to ensure that medicines used by children are specifically authorized for that use and with appropriate forms and formulations and ensure the availability of high quality information about treatments used by children. Similar initiatives in other countries and continents may evolve in the future.4 For example, the European Union (EU) Pediatric Regulation3 aims to facilitate the development of medicinal products for children by outlining obligations and offering incentives for the pharmaceutical industry.

The regulation requires that the development program for any new pharmaceutical product for adults must include a Pediatric Investigation Plan (PIP); a plan for pediatric clinical trials or an agreed waiver to PIP if the product is unnecessary or unsafe for children. The PIP is needed for products that have a valid Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) or a valid patent that qualifies it. Proposals for PIPs are submitted to the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pediatric Committee (PDCO), which is responsible for assessing and agreeing to or rejecting the plan.5 This PIP requirement is same for all products irrespective of the intention to develop the product for children or only for adults. Without a waiver or compliance with PIP, no marketing authorization (MA) is granted for adult products. The reward for PIP is a six-month extension to the patent or SPC (or two-plus years for orphan products).

The PIP is a complete development program, including all MA details of measures for demonstrating quality, safety, efficacy, and age-appropriate formulation(s), taking account of each condition or indication for each pediatric subset, in addition to age groups between 0 and <18 years. Specific timelines for start and completion of each study, and additional pharmacovigilance plans for long-term follow-up are included, although modifications are possible. The PIP is binding on companies and leads to a compliance check by the PDCO. Industry should submit the PIP no later than at completion of the human pharmacokinetic studies (Phase I in adults). The PIP increases the need for knowledge about pediatric pharmacology, pediatric formulations, clinical trial methodology, practical pediatric clinical trial expertise, and suitable trial sites. Scientific advice given by EMA/PDCO for companies regarding PIPs is free of charge, but additional advice can be sought from specialized clinical trial networks.

The European Network of Pediatric Research at the European Medicines Agency (Enpr-EMA)6,7 was established in 2011 according to the Pediatric Regulation [Article 44]. Enpr-EMA is a network of research networks, facilitating collaboration with members from within and outside the EU, including academia, pharmaceutical industry, regulators, and the PDCO. The Enpr-EMA members (currently 35 networks) include national, age-, and disease-specific networks.8,9,10,11,12,13 To be accepted as a member (membership categories 1-4), a network must demonstrate that it fulfills defined recognition criteria such as research experience and ability, organization, processes, competencies, ability to provide expert advice, and public involvement. Category 1 networks fulfill all minimum quality criteria and are part of the operational center of Enpr-EMA, sharing responsibility for the network's long- and short-term strategy.

A report to the European Commission for the year 2014 on companies and products that have benefited from the rewards and incentives of the Pediatric Regulation and on companies who have failed to comply with any obligations highlighted that there are ongoing regulatory challenges for the pharmaceutical industry, seen in relation to PDCO decisions resulting in delayed timelines, to PIPs and annual reporting of the deferred PIP trials or planned PIP progress.16,17,18 In the latest EMA annual report (2013), the proportion of delayed PIP applications (six months or more) was about 20% and the time lag for submissions and for full waiver applications was over two years on average. Additionally, 31% of PIPs scheduled to be completed by June 2013 were not completed in time and did not have any justifications or agreement to change the timelines. The annual report cites several problems as reasons for PIP deferrals, such as recruitment difficulties (28.4%), other (non-specified) reasons (19.4%), problems with national competent authorities (9.1%) and similar problems with ethics committees (7.5%). In addition, safety concerns were mentioned in 15 reports (4.7%).17

Currently, only a few published articles relate to communication between pediatric clinical trial networks and the pharmaceutical industry and conclude that most of the delays and difficulties are avoidable by using specialized networks more effectively.19,20,21,22 However, there are no publications on industry expectations of networks, or other pediatric clinical trial networks’ capabilities, funding, and resources related to industry services. While there is a need for both pediatric clinical trial networks and the industry to have access to information about new pediatric products and clinical trials, capacities and required services, the Enpr-EMA networks would also like to increase their visibility and make contact with pharmaceutical companies involved in pediatric clinical trials.

To fill this gap, the Enpr-EMA set up a working group (WG) including member networks and active stakeholder representatives to identify strategies to improve and facilitate communication between the pediatric clinical trial networks in Enpr-EMA and the pharmaceutical industry and to develop recommendations on how to do this. The WG conducted two surveys between December 2013 and February 2014 and collected data on pharmaceutical industry partners´ and the Enpr-EMA networks´ experiences, examples of good practice, challenges, and ideas for communication and visibility. This paper summarizes the survey results, including a minimum set of capabilities required to develop an ideal network, and additional recommendations for both industry and Enpr-EMA.

Methods

Industry survey

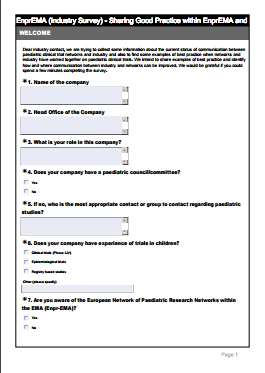

A web survey of 13 questions was sent via e-mail to over 600 industry contacts between Dec. 13, 2013, and Feb. 14, 2014 (click on box at right to view survey questions).

Network survey

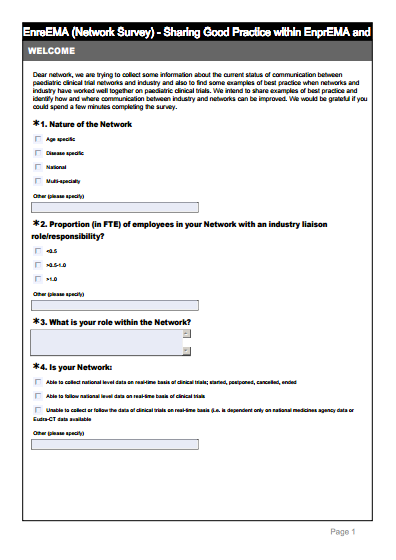

A web survey of 11 questions was sent via e-mail to all Enpr-EMA Category 1-2 member networks (N=20) between Dec. 13, 2013, and Feb. 14, 2014 (click on box at right to view survey questions).

The survey data was analyzed in two ways; structured answers as quantitative summary of results and open answers by categorization and listing according to the authentic answers and recurrent themes. Afterwards, final analysis was carried out extracting descriptive background information that was put into context with existing knowledge. Based on this analysis, recommendations were created for Enpr-EMA, its networks, and the pharmaceutical industry.

Industry survey results

Profile of the responded companies

The survey resulted in 70 responses from a variety of companies, including large pharma, biotech, consultants, and CROs (see Table 1). In five cases (7%), there were several responses from the same company, but the respondents had different roles, departments, and office locations.

The majority of responses came from large companies actively involved in conducting pediatric clinical trials; 71% were from a company with a pediatric council. The majority (66%) were already aware of Enpr-EMA, although only 46% had worked (either personally or their company) with Enpr-EMA or another clinical trial network. The majority of the respondents (90%) said they had experience with Phase I-IV clinical trials, while 23% and 34% had experience in epidemiological- and registry-based studies, respectively. Most of those responding were actively involved in conducting pediatric clinical trials and only a minority (19%) had little or no experience within their current company.

Benefits, challenges of collaboration with networks

Generally, the pharmaceutical companies (i.e., network users) highlighted that clinical trial networks are very valuable and beneficial in providing different services to the pharmaceutical industry, as long as all the basic elements behind the services have been organized and managed in a proper way. According to the companies, these basic elements include the following:

- Appropriate timelines with standard operational procedures within the network

- Clear information about what is included in the services and what is not

- Sufficient resources (funding, personnel)

- Well-established communication system between clinical (scientific) experts of the network and network management

- Accurate public information about the available services

Some of the companies identified additional benefits that they gained from using clinical trial network services. These were 1) Internal benefit; more confidence with the clinical development program, and 2) External benefit; the opportunity to optimize the development of the clinical trials, to recruit patients via highly skilled and motivated investigators and to guide the company through perceived pitfalls with trial feasibilities. In addition, companies valued the opportunity to establish an electronic database of physicians who agreed to be in it. The responders also appreciated the benefit to patients, “who could be treated outside her/his country through network collaboration.” The complete list of identified benefits is in Table 3 ahead.

Despite the positive experiences, companies also described challenges with networks. The general theme of the problems was detected as lack of consistency and uniformity, and limited resources. For users, the term “network” has different meanings and appears in different levels of organization and ability to manage studies, and, therefore, it is unclear which services each network can provide. Only well-known, well-established networks with regular funding can prove efficacy and strong operational status.

The users stated that they have had difficulties in finding the right networks to work with. Most of the networks in Europe are still virtually unknown with respect to therapeutic areas, competence, expertise, and contact information. Furthermore, limited resources in funding, personnel, protected time for clinicians as investigators or experts prevent equal services. For users, it is difficult to understand these differences between networks. Additionally, comparing the user´s needs, there is insufficient global interaction (U.S. and EU) of operations within the networks, and between the networks in Europe. There is also a huge variation of management systems and organizational administration procedures between the individual networks, and a lack of common principles and standardized procedures for confidentiality and for reimbursement within the networks.

Ideas to improve communication

To address the given mandate by Enpr-EMA, the WG wanted to identify new ideas for developing better communications and examples of best practice to improve the current situation. For this, 43 (61%) of the responded companies gave their suggestions as how to identify appropriate clinical trial networks, and how to improve contacts and communication with these. The majority of these responders (39%) suggested communication via EMA or Enpr-EMA website or database, or by using EU Commission website. The second highest suggestion (23%), was to create a separate website or database and Internet portal with an online directory for searching networks. Other answers included options such as conferences, workshops, meetings, contacts via associations, patient organizations, clinical organization or CRO contacts, and additionally through publications, clinical trial registries, and direct contacts to sponsors.

For better visibility, the companies proposed the following actions to be taken by the networks:

- Advertise on Enpr-EMA website with quick access to the networks with identification of therapeutic areas of interest

- Ensure each network has a central coordinating office and an individual homepage with information on the possibility to obtain expert advice (PIP)

- Improve the process through the establishment of clear boundaries and response timelines

- To have clear confidentiality rules and create a template for initiating the contact with the networks

- Nominate person(s) within respective network(s) as member(s) of the scientific associations

- Create ability of the network to work globally (links/interactions also outside EU)

- Provide dedicated staff to actually run clinical trials

Network survey results

Profile of the responded networks

Due to a blinded questionnaire, the results do not include identification of the responded networks. The survey was sent to 20 Enpr-EMA Category 1-2 member networks (see Table 2) and of those 16 responded. Of these, 50% were multi-specialty clinical trial networks (i.e. representing many therapeutic areas). Of all networks, the distribution was between disease specific (44%), age specific

(25%), and national (31%) networks. The majority (63%) had less than 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) working with a role as industry liaison. Funding for networks was reported as being received from national governments or ministries (25%), several funding parties (38%), and hospitals (19%) or charities (13%). Half (50%) of the networks informed us they also received funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Regarding the data on the number of recruited trial subjects for a new trial, a minority of the networks were able to collect this data on a national level (38%), or follow national data with access to the required databases (31%). Half of the networks (50%) were dependent on the national Medicines Agency or European Clinical Trials Registry (EudraCT) data. The most common services provided by the networks, were site identification (80%), protocol development (74%), and feasibility assessments (67%). Some networks also provided support for the design of research protocols and reviewing the content of patient information (53%), and some were able to support trial setup (40%). Fewer networks offer services of research governance (33%), nursing (27%), and pharmacy support (20%). The proportion of commercial trials that a network supported varied from 0% to 100%. Of the responders, six reported that the proportion of commercial trials was between 20% to 60%, while this proportion was under 10% in four networks and over 60% for the rest of networks.

Benefits and challenges of collaboration with pharma

The survey included a question about the benefits that networks had gained when working with the pharmaceutical industry and asked them to provide some examples of good practice. Networks felt generally, that when industry had taken account of the network advice on protocol development, it had resulted in more robust and feasible protocols, reducing the burden on patients whenever possible. Commercial trials are well resourced with sufficient consumables, patient data recording, reporting facilities, and travel expenses. Many of the networks shared positive experiences with the feeling of involvement in the development processes and with open and relevant communication. Additionally, the networks felt that when studies had proper resources, both parties met their shared objective in recruiting to target within the required timescale. However, the variability in funding led to variability in the remit of the networks and the support they can provide.

Although working with the pharmaceutical industry brought valuable financial resources to the networks, it brought challenges as well, such as unrealistic timelines for feasibility, lengthy “Expression of Interest” questionnaires with limited or restricted trial information for investigators to do this, and a lack of communication, information, and feedback to sites that had completed feasibility but had not been selected to participate. The complexity of working with both CROs and pharmaceutical companies was also reported as an area leading to difficulties when further information is required or decisions have to be made. Additionally, the networks experienced lack of clarity between the role of the CRO and sponsor when issues arose, such as around information technology.

Other challenges related to protocols and PIPs that were designed without considering the sensitivities in working with small children; protocols more intensive than parents would accept and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies not always offering a direct patient benefit, causing difficulties in patient recruitment. Some protocols had a heavy burden in terms of long and frequently administered quality of life questionnaires, tensions around additional safety data required for already marketed products, and very restrictive eligibility criteria that did not always consider real therapeutic needs. In the area of mental health, the networks responded that industry often showed reluctance to conduct comparator studies.

Recommendations to all parties

These results allowed the WG to create specifications for an “ideal pediatric clinical trial network” in order to provide the best possible coverage and services for the pharmaceutical industry. After classification, the responses were divided into eight categories:

- Scientific Expertise

- Feasibility Assessment

- Patient/Investigator Involvement

- Legal Advice/Administration & Management

- Training

- Communication

- Resources

- Timing

These include desired network capabilities and services identified by the companies, to be used for network development processes (Table 3).

Finally, after network capabilities the WGs formulated the summary of the survey results as recommendations for all parties involved in this survey (Table 4).

Discussion

These surveys show that communication with networks is generally perceived as beneficial, if all the basic elements behind the network services have been organized and managed in a proper way. Furthermore, both industry and pediatric clinical trial networks are interested and committed to further collaboration. Many of the networks reported that when there was good communication links with industry, it was a positive experience resulting in more efficient identification, set up of sites, and start of new trials.

The reality, that after eight years of the EU Pediatric Regulation, several regulatory challenges still exist, reinforces the fact that clinical trial networks are underutilized and pharma needs earlier communication with networks to avoid problems and enhance the situation. The company answers included several realistic and feasible options; the most commonly requested network information to be provided by Enpr-EMA has already been addressed by the new public Enpr-EMA Network Database, including search options and requests for feasibility.

While this is true, the Enpr-EMA networks supporting pediatric clinical trials in Europe are diverse and still mainly unknown by industry due to limited information. In addition, clinical trial networks have different organizational models, funding, management, and administration systems, creating a lack of common principles and information on practical procedures. Fulfilling the listed ideal services is very dependent on network resources-both financial and the number of FTEs. Network legal status, national regulations, pricing practices, and confidentiality requirements determine the practice for the network´s capabilities, administrative procedures, contracts, and costs. Very often the networks are unable to have any influence on regulations behind these differences.

Since Enpr-EMA Self-Assessment criteria for the member networks do not include detailed information on the capability of each network, it is difficult also to identify common strategies. It will take time before existing members of Enpr-EMA can all provide a similar level or range of services, or provide global interaction between the clinical trial networks in Europe. Nevertheless, all clinical trial networks can currently offer high-level scientific expertise and practical knowledge about local medical practices and trial site resources. In the UK, there are national costing templates, contract, and CDA templates accepted in England and Scotland with modifications for national laws; informed consent templates for children for EC submission are available in Finland.

Conclusion

Lack of awareness, incongruent expectations, and insufficient communication have caused suboptimal collaboration and challenges for pediatric clinical trial networks and the industry. Early consultation results in efficient clinical trial strategies, reduces the burden on patients and families, and improves patient recruitment, leading to feasible and realistic agreements and timelines for both networks and industry. To streamline service processes, the communication about industry needs and expectations should start as early and be as clear as possible. All of the current network services could be exploited more effectively with better communication with industry.

The pharmaceutical industry needs more information links and contacts to pediatric clinical trial networks. With the continued support of Enpr-EMA, pediatric clinical trial networks could develop standardized procedures and ideal services. Inevitably, to reach the ideal capabilities, most of the pediatric clinical trial networks need more core funding for developing their services.

In conclusion, the WG hopes to support the development of all Enpr-EMA networks and encourage the pharmaceutical industry to consider using pediatric clinical trial networks more, in order to have higher quality clinical trials, potentially leading to better medicines for children and young people in Europe.

* Pirkko Lepola, with Finnish Investigators Network for Pediatric Medicines, Clinical Research Institute Helsinki University Central Hospital Ltd., Finland, email:

* To whom all correspondence should be addressed

Acknowledgements:

The original Enpr-EMA nominated working group included several other people who assisted with the preparation of the initial survey questionnaires. We want to thank the following people for providing help that greatly improved the final survey: Dr. Christina Peters (EBMT, Austria), Dr. Richard Trompeter (GOSH, IPTA, UK), Mrs. Lynda Wight (TOPRA, UK), Dr. Klaus Hartman (Biomedpark, Germany). Additionally, we want to give special thanks to Dr. Stefanie Breitenstein (Bayer Pharma, Germany) for reviewing the final draft document.

References

1. Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, Public Law 107-109, January 4, 2002. Available at:

2. Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003, Public Law No: 108-155, January 7, 2003. Available at:

3. Regulation (EC) no 1901/2006 of the European parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for pediatric use and amending the regulation (EEC) No 1768/92, Directive 2001/20/EC, Directive 2001/83/EC and regulation (EC) No 726/2004.Official Journal of the European Union 2006; L 378: 1-19. Available at:

4. Hoppu K, Anabwani G, Garcia-Bournissen F, Gazarian M, Kearns GL, Nakamura H, Peterson RG, Sri Ranganathan S, de Wildt SN.; The status of pediatric medicines initiatives around the world-What has happened and what has not? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Jan;6 8(1):1-10.

5. European Commission. Guideline on the format and content of applications for agreement or modification of a pediatric investigation plan and requests for waivers or deferrals and concerning the operation of the compliance check and on criteria for assessing significant studies (2014/C 338/01). Available at:

6. European Network of Pediatric Research at the European Medicines Agency (Enpr-EMA). Available at:

7. Ruperto N, Eichler I, Herold R, Vassal G, Giaquinto C, Hjorth L et al. A European network of pediatric research at the European Medicines Agency (Enpr-EMA). Arch Dis Child. 2012; 97: 185-188.

8. Jacqz-Aigrain E, Kassai B, CICP Network. The French Network of Pediatric Clinical Investigation Centres (CICPs). Assessment of activities over a three year period, 2004-2006. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther 2007;8:40-5

9. Korppi M, Lepola P, Vettenranta K, Pakkala S, Hoppu K.; Limited impact of EU pediatric regulation on Finnish clinical trials highlights need for Nordic collaboration.; Acta Paediatr. 2013 Nov;102(11):1035-40.

10. Nunn T.The National Institute for Health Research Medicines for Children Research Network. Paediatr Drugs. 2009; 11:14-15.

11. Ruperto N, Martini A. Networking in pediatrics: the example of the Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO). Arch Dis Child. 2011. Jun;96(6):596-601.

12. Seibert-Grafe M, Butzer R, Zepp F.; German Pediatric Research Network (PAED-Net); Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11(1):11-3.

13. Weber EH, Timmermans IT, Offringa M.; The Dutch Medicines for Children Research Network: a new resource for clinical trials.; Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11(3):161-3.

14. Rose AC, Van’t Hoff W, Beresford MW, Tansey SP. NIHR; Medicines for Children Research Network: improving children’s health through clinical research. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 6(5), 581–587 (2013).

15. Rose A., Beresford M.,Tansey S. NIHR Medicines for Children Research Network: Supporting the delivery of Pediatric Clinical Studies. Pharmaceutical Physician, May 2013, vol.23; 6: 6-10.

16. 5-year Report to the European Commission. General report on the experience acquired as a result of the application of the Pediatric Regulation. 8 July 2012, EMA/428172/2012, Human Medicines Development and Evaluation Human Medicines Special Areas Sector. Available at:

17. European Medicines Agency, Pediatric Medicines Office. Report to the European Commission on companies and products that have benefited from any of the rewards and incentives in the Pediatric Regulation and on the companies that have failed to comply with any of the obligations in this Regulation. 9 September, 2014. EMA/24516/2014, Corr.3. Human Medicines Research and Development Support Division. Available at:

18. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Progress Report on the Pediatric Regulation (EC) N°1901/2006. COM (2013) 443, FINAL. Better Medicines for Children - From Concept to Reality. Available at:

19. Turner MA, Catapano M, Hirschfeld S, Giaquinto C; Global Research in Pediatrics; Pediatric drug development: the impact of evolving regulations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014 Jun;73:2-13. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.003. Epub 2014 Feb 18.

20. Nass SJ, Balogh E, Mendelsohn J. A National Cancer Clinical Trials Network: Recommendations from the Institute of Medicine. Am J Ther. 2011; 18: 382–391.

21. Thomas KS, Koller K, Foster K, Perdue J, Charlesworth L, Chalmers JR. The UK clinical research network-has it been a success for dermatology clinical trials? Trials. 2011; 12: 153. Published online 2011 June 16. Available at:

22. Schmiegelow K, Forestier E, Hellebostad M, Heyman M, Kristinsson J, Söderhäll S. et al.; Nordic Society of Pediatric Haematology and Oncology. Long-term results of NOPHO ALL-92 and ALL-2000 studies of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010; 24:345-354.

Newsletter

Stay current in clinical research with Applied Clinical Trials, providing expert insights, regulatory updates, and practical strategies for successful clinical trial design and execution.