Optimizing the Process for Adopting DCT Solutions

Study uncovers realistic goals in efforts to embrace decentralized clinical trials.

There have been a number of occurrences of late signaling that the adoption of decentralized clinical trial (DCT) technologies is far from a fait accompli. To name a few:

- A February 2023 assessment of ClinicalTrials.gov listings conducted by IQVIA found that only 1% of industry-sponsored clinical trial starts are using DCT solutions.

- This spring, DCT providers reported stalling revenue, cited market resistance, and announced layoffs and restructurings.

- A recent Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (Tufts CSDD) study found that sponsor-reported use of virtual and remote solutions in active clinical trials had fallen well below the levels reported by sponsors during the first year of the pandemic.

Lengthy and bumpy timelines associated with the adoption of any innovation supporting clinical trial execution are not new. Tufts CSDD research has shown that the typical adoption cycle for a single company takes a full six years; 20+ years for the drug development industry to achieve wide-spread adoption, defined as 67% or more of companies routinely using an innovative solution.

This article reflects on Tufts CSDD’s research characterizing the innovation adoption process in drug development to shed light on and share insights into what we can more realistically expect for DCT solutions adoption moving forward.

Two frameworks

A pair of conceptual frameworks—Everett Roger’s Innovation Diffusion Model and the Gartner Group’s Hype Cycle—set the stage for understanding the dynamic nature of innovation adoption. The former, introduced in 1962, suggested that within companies and across an industry, there are varying levels of opportunistic behavior and aversion to risk.

Individuals and organizations that are highly receptive to risk, keenly aware of and willing to act quickly on the need to innovate are called “pioneers” and “early adopters.” Those organizations that are highly risk averse, lacking awareness and slow to act are characterized as “late majority” and “laggards.”

The Gartner Hype Cycle, introduced in 1995, focused on the evolution of expectations associated with a given innovation. Individuals and companies first look at an innovation with unrealistic and exuberant expectations that contribute to initial adoption perceptions. As organizations gain real-world experience with an innovation, their expectations plateau at the “peak of inflated expectation” and fall precipitously into the “trough of disillusionment” where they must temper and revise their expectations. Over a protracted period of time, expectations align with reality when organizations begin to realize the true benefits and value of an innovation.

Drug development professionals have noted the unprecedented—and, for some,—irrational —level of excitement that followed early use of virtual and remote solutions at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Innovation adoption stages

In 2022, Tufts CSDD undertook an empirical study to gather granular data on innovations supporting all aspects of clinical trial execution, including protocol planning and design; investigative site selection and management; study initiation, ongoing trial management and closeout; patient screening, enrollment and retention; administration of protocol procedures; and data collection, management, analysis, and reporting. Innovations in biomedical science and pharmacology fell outside the scope of this study as they occur largely within scientific functions and do not require cross-functional changes, integration, and coordination in operating practices, procedures, and processes.

A working group of 17 companies provided input into defining areas of focus; designing an interview guide and survey instrument; and discussing preliminary study results and their implications. Tufts CSDD conducted a global survey that yielded 631 total responses from approximately 225 distinct companies—90% biopharma; 10% contract research organizations(CROs). Among respondents, there was good representation by company size, geographic location of company headquarters, and therapeutic area(s) of focus (e.g., 62% focus on oncology; 25% on immunology and infectious diseases, 16% on cardiovascular diseases, 14% on neurological disorders, and 7% on rare diseases). Nearly half of respondents indicated having a role in a clinical operations function. The highest percentage (54%) operates within a large pharmaceutical company, 28% in mid-sized, and 18% in small companies. Half (49%) are based in Europe and 39% are based in North America.

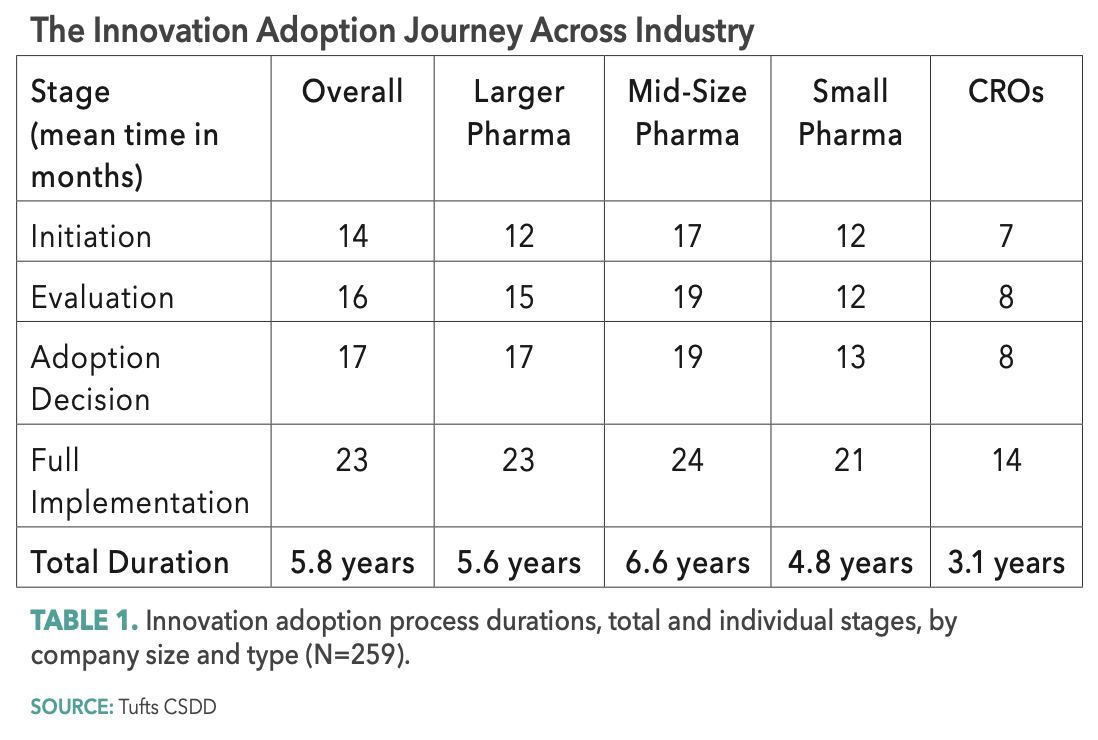

The overall time to adopt an innovation supporting clinical trial execution is 70 months, on average, or 5.8 years. Approximately 20% of the total time—13.8 months—is spent in the initiation stage where organizations are identifying and characterizing an operating need, gauging organizational interest and initiating plans to assess an innovation. One-out-of-10 respondents rates this as the most difficult stage, citing major challenges associated with building cross-functional support and coordination and the absence of regulatory clarity. Another challenge cited is the misalignment of incentives that dissuade personnel and functions from embracing risk and novel solutions.

In the next stage—evaluation—organizations identify, qualify, and engage solution providers; and pilot and evaluate various innovative solutions. This stage takes, on average, 15.7 months, or 23% of the total adoption cycle. A similar one-out-of-10 rates this stage as the most difficult. Poorly designed and executed pilots, the failure to gather sufficient evidence to assess and compare innovative solutions, and the inability to generalize across the portfolio and demonstrate ROI are cited as the largest challenges in this stage.

Industry observers and insiders have noted that the rapid adoption of DCT tools necessitated by the pandemic substantially compressed the initiation stage and invariably skipped the evaluation stage. In the wake of the pandemic, organizations have regrouped and are looking to conduct considerably more thorough evaluation and ROI assessment.

The third stage involves making the decision to move forward and fully adopt an innovative solution. In the adoption decision stage, organizations review their pilot experience, build internal consensus to move forward with, and announce an enterprise-wide implementation. Arriving at an adoption decision takes nearly 17 months, or one-quarter of the total innovation adoption cycle time. One-third of respondents believe that this is the most difficult stage, citing uncertainty and internal dynamics and politics associated with having insufficient “evidence” to support management’s decision to implement.

The final stage—full implementation—takes, on average, two years and represents one-third of the total time to adopt an innovative solution. This stage entails implementation planning, roll-out, communication, training, monitoring, and continuous improvement. Nearly half (47%) of all respondents rate this stage as the most difficult, citing several major challenges, including the lack of senior management and cross-functional support and engagement; poor regulatory clarity and support resulting in substantial concern and resistance from regulatory and legal affairs functions; the absence or late preparation of a comprehensive change management plan to guide the organization through full implementation; and failure to provide the necessary investment of time and resources to fully support the transition from adoption decision to full implementation.

Adoption process variation

Mid-size companies take the longest time—on average, 6.6 years—to complete the innovation adoption process. Small companies are nine months faster than larger companies and nearly two years faster (21 months) than mid-size companies. CROs are able to complete the innovation adoption process in nearly half the time—3.1 years compared to 5.8 years for pharma companies (see Table 1 below). Indeed, a significant speed advantage and much lower variation around mean durations are observed among CROs at each innovation adoption stage compared to that of pharma companies.

Small companies—and most notably CROs —bring speed advantages to the innovation adoption process but for different reasons. They are generally more nimble than their larger counterparts with less siloed functional relationships and with personnel often responsible for cross-functional activities. With more constrained capital and resources, and pressure from outside investors, smaller companies must often take more risks and arrive at decisions faster. For CROs, executional innovation is central to their ability to differentiate their services and capabilities and retain their clients.

A much higher proportion of mid-size and small companies rates the initiation and evaluation stages as “most difficult.” Mid-size companies in particular are more likely to positively rate their ability to complete each stage in the process.

Whereas 10 years ago a larger proportion of companies centralized their innovation adoption functions, only 15% of companies today report using a centralized, dedicated function to drive innovation adoption. The majority (85%) reports using a decentralized approach today, relying on individual functional areas to promote, pilot, and evaluate new operating innovations.

Lastly, most companies are harsh self-critics of their ability to adopt innovative solutions supporting clinical trial execution. Approximately one-third (31%) rate the overall adoption process within their organization as “poor” or “very poor.” Nearly 80% perceives that the process takes “somewhat’ or “much” longer than expected and 61% believes that the process for their organization takes longer than it does for their peers. Larger companies are more likely to perceive this.

The drug development industry has long placed a premium on innovations that drive differentiation and competitive operating and performance advantages. As stakeholders throughout the clinical research enterprise look in earnest to accelerate drug development timelines, the ability to quickly, efficiently, and effectively adopt novel solutions supporting clinical trial execution and improve patient engagement is paramount. Although the stages in the adoption process —from initiation to full implementation—are rational and necessary, the relative speed of small pharma and CRO companies offers insight and indicates opportunities to optimize the innovation adoption process.

Newsletter

Stay current in clinical research with Applied Clinical Trials, providing expert insights, regulatory updates, and practical strategies for successful clinical trial design and execution.

What Can ClinOps Learn from Pre-Clinical?

August 10th 2021Dr. Hanne Bak, Senior Vice President of Preclinical Manufacturing and Process Development at Regeneron speaks about her role at the company as well as their work with monoclonal antibodies, the regulatory side of manufacturing, and more.

2025 DIA Annual Meeting: Why AI and Automation Are Set to Become the New Normal in Clinical Research

June 20th 2025Peter Ronco, CEO, Emmes, shares his long-term vision for artificial intelligence in clinical research, from making automation routine to improving drug discovery, transforming regulatory oversight, reducing animal testing, and promoting ethical, equitable data use worldwide.