Establishing a Basis for Secondary Use Standards for Clinical Trials

Study seeks to understand how different forms of data meet the needs of researchers.

Secondary use of individual patient data (IPD) generated through a randomized clinical trial (RCT) represents some of the highest-quality research data available. Clinical trial data is collected with the patient’s consent from trials designed with clearly defined endpoints derived from objective assessments. Effective reuse of these data has the potential to transform the clinical research process, improve trial design and execution, and respects the patients who donate their time and their data as part of the clinical development process.1

The transformative potential of effective data reuse has resulted in calls from groups including the World Health Organization,2 the National Institutes of Health,3 the G7,4 regulators,5 and patient advocacy groups for sponsors to openly share and reuse clinical trial data. However, achieving widespread use of clinical trial IPD also requires data contributed by trial sponsors to retain as much research utility as possible. A trial sponsor’s data sharing policies determine what data and supporting documentation to share, where and how that data will be shared, and what data transformations are needed (e.g., to protect patient privacy or intellectual property).

The policies applied to secondary use data contribution have a direct impact on determinants of research utility. These determinants include data comprehensiveness and completeness;6 the supporting documentation and contextual information provided (e.g., transformation reports and data dictionaries); and the metadata to aid end-users in determining whether the contributed data will be fit for purpose for the intended research use.

Across trial sponsors, there is significant variability in data sharing policies and applied data protection methodologies.7 This variability creates substantial challenges for Data Sharing Platforms (DSP) and their end-users, especially when research use cases require pooling or integrating IPD from multiple sponsors. This, therefore, hinders efforts to make the shared data “FAIR” (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable).8

Two dimensions influence how well the data sharing ecosystem serves the needs of the research community. The first of these dimensions is access. Access can be thought of as the number of trials available for secondary use from a given sponsor and on a given DSP in conjunction with the DSP policies that govern research access.9,10

The second dimension and focus of this paper is data utility, or how well contributed data meets the needs of researchers. While this paper focuses on the needs of the researcher, the results are also important for data contributors. Data contributing organizations are often consumers of data. This is particularly true for biopharma sponsors, many of whom have made significant investments in internal data sharing platforms bringing together a sponsor’s internal data and data from external data sources.11 Besides being a potential end-user beneficiary of a well-functioning data sharing ecosystem, data contributors may also benefit by better meeting the research community's needs and thus ensuring their investment in data sharing infrastructure delivers a maximum return to the community.

Objectives:

- Understand key factors of research utility for users of secondary-use clinical trial datasets containing IPD.

- Determine the relative value to researchers of various types of IPD datasets, supporting documents, and metadata as a basis for future secondary use data standards designed to maximize the research value of clinical trial data.

- Identify gaps in researcher or data contributor knowledge that present opportunities for community education.

Methodology

Scope

The research scope included surveying information and elements that may be available to end-user researchers accessing or using secondary IPD clinical trial data irrespective of therapeutic area and specific research objective. These areas included:

- Datasets: What patient-level datasets are needed by researchers?

- Documents: What trial-specific supporting documents do researchers need to enable secondary use and maximize research value?

- Metadata: What information about the trial is needed to provide sufficient context for dataset access and use?

- Timing: When is the provision of selected supporting documents and metadata needed to facilitate process efficiency for both data contributors and researchers?

Other areas that may impact research use and utility were out of scope. Specific research use cases may impact the information and elements required by IPD end-users; however, exploring the nuances of specific use cases was out of scope. The authors did not examine the research impact of dataset or documentation content or completeness. The area of patient consent and/or legal basis for data contributions was not included because, while relevant to data contributors,12 it was deemed to be outside the general scope of end-user considerations. The Data Protection methodology applied to the processing of datasets and documentation is an important determinant of data utility13 but was not included in this research because the process steps are generally not evident to the contributed data end-user. Information about the result of the data protection process (e.g., a variable-level transformation report) is included in the research scope.

Survey conceptualization, distribution, and data collection

The survey design goal was to determine which elements of data contribution are important to IPD end-users. The survey was designed to accommodate a range of Data Sharing Platform (DSP) access models, ranging from controlled, gated, or organization-only (internal) access to open data sharing platforms. The target audience was DSP end-users who requested, downloaded, accessed, or used clinical trial datasets containing IPD for secondary research purposes.

The survey content was derived by collating the datasets, documentation, and collected metadata for secondary clinical trial contributions across multiple DSPs. Survey questions were divided into three areas:

- Demographics: The respondent’s role, experience level, and general secondary use case(s) for contributed clinical trial data containing IPD.

- Contributed Trial Content: What clinical trial datasets, supporting documentation, and metadata are needed to support the respondent’s intended use(s)?

- Recent Experience: Information about the respondent’s most recent DSP interaction

The survey responses were returned anonymously. However, respondents had the option to provide contact information, and, in some cases, verbatim responses included information that could identify the respondent and/or their organization.

Survey distribution represented both academia and industry and encompassed the spectrum of DSP access models. The survey was distributed to relevant research communities through multiple DSPs, biopharma companies, and non-profits. Due to the breadth of distribution, which may include organizations or channels the authors were not aware of, a list of distributing organizations is not provided. In some cases, organizations were provided with an organization-specific survey version to allow for subsequent comparison of their respondent population to overall responses. All distributed survey versions were identical. Other distribution included CRDSA newsletters, social posts (LinkedIn), and conference mentions.

Analysis plan

Prior to analyses, the data from all organizational surveys were merged into a single master dataset. All respondent identifiers were anonymized by removing or redacting identifying information, including within verbatim responses and email addresses (if provided).

All analyses were carried out using Google Data Studio.14 The data variables were grouped into nominal categories (categorical variables). All responses were summarized with descriptive statistics (number and percentage of responses to the different nominal categories), and no statistical hypothesis testing was carried out.

Demographic sub-groups with similar characteristics were consolidated into categories to enable the interpretation of responses. Organization types were consolidated into three categories for response analysis:

- Academic/Non-Profit (Survey response of Academic Research Organization, Non-Profit or Foundation, Individual Researcher, Scientific Interest Group)

- Biopharma (Survey response of biopharma)

- Service/Technology Vendor (Survey response of CRO, Service Partner, Technology Vendor)

To facilitate comparison by organization type when assessing responses to the survey questions, the results for organization types with low response frequencies were not presented when the sub-group had consistently similar response characteristics to another sub-group and are only presented when different in response. The computed total frequencies, however, were inclusive of all sub-groups.

The secondary use data experience level was also grouped into three categories and relative frequencies were computed for the different organization types.

- One time user

- Moderately experienced

- Very experienced/power user

Survey responders who identified themselves as “Power Users” or “Very Experienced” were combined into a single group.

Respondents were asked which DSPs they use. Respondents could select or enter multiple DSPs. To allow for analysis of the responses to all data sharing platform engagements (single or multiple), responses were grouped into five ordered categories:

- Less than 1 time a year

- 1-2 times a year

- 3-6 times a year

- 7-12 times a year

- More than 12 times a year

The frequency of engagement was then computed and compared across the different organization types.

Further, response analysis of data sharing platform usage (single or multiple) was done by first applying SAFE data platform categorization per Bamford, Arbuckle et al. “Sharing Anonymized and Functionally Effective (SAFE) Data Standard”15 and then computing the frequencies of responses for the different organization types. See Appendix A for the list of Data Sharing Platforms (inclusive of free text responses) included in the analysis (inclusive of free text responses).

The purpose of data request/usage such as peer reviewed journal publication on new knowledge or insights, informing clinical trial design, generating safety or adverse events reports and to supporting investigational new drug applications (IND) were categorized into three groups: Academic research/publications, internal organization use, and regulatory submission. To allow for further descriptive analysis, responses were categorized as:

- N/A

- Primary use

- Occasionally

- Frequently

The frequency of usage (number and percentage) were computed for each organization type.

The number of studies requested (expressed in percentages) and the relative usability frequency or yield, as well as the reason for non-use and their frequencies, were also calculated. The usage yield was then grouped or categorized by respondent experience level to allow for comparative analysis.

Dataset types such as ADaM, SDTM and data model description documents such as data dictionaries as well as study supporting documents (e.g study protocol) are key components of secondary use data requests. Supporting documents provide context to the supplied IPD datasets and aid the researcher in understanding trial design and execution factors that may impact their research use.

Respondents were asked to assess datasets and document types that may be supplied by data contributors and assign each to four ordered categories: Mandatory for Use, Important, Useful, and Not Relevant/Not Required, and the percentages were calculated for the responses for their importance for secondary use. For analysis purposes, Mandatory for Use and Important have been grouped into a single Mandatory/Important category.

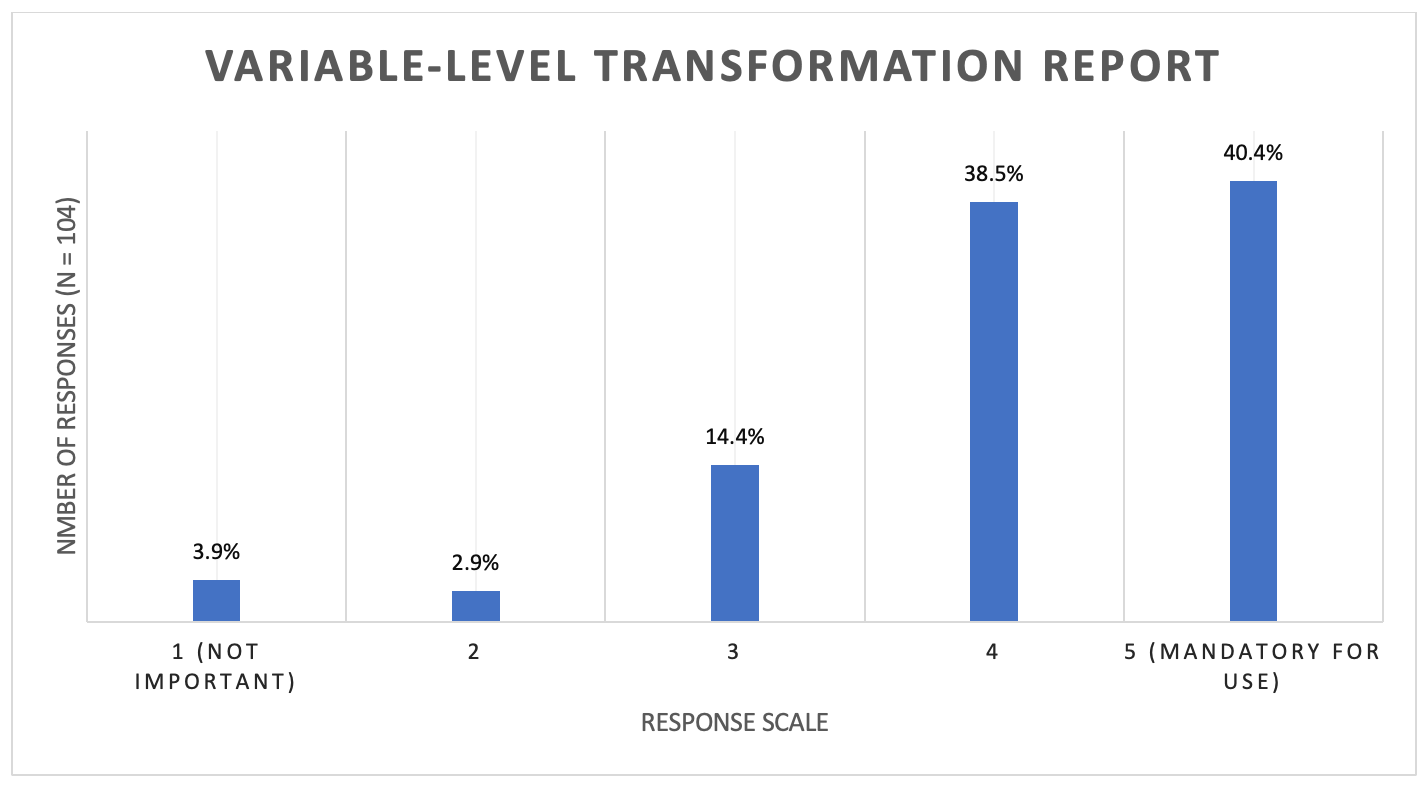

The authors are aware that certain sponsors furnish a study-specific data transformation report documenting the transformations at a variable level that took place during the data contribution anonymization process. The authors understand that this type of data transformation report is not routinely or uniformly provided by data contributors. To evaluate the value to the research community, Respondents were asked to assess the importance of this type of report on a 1 to 5 scale from Not Important (1) to Mandatory for Use (5).

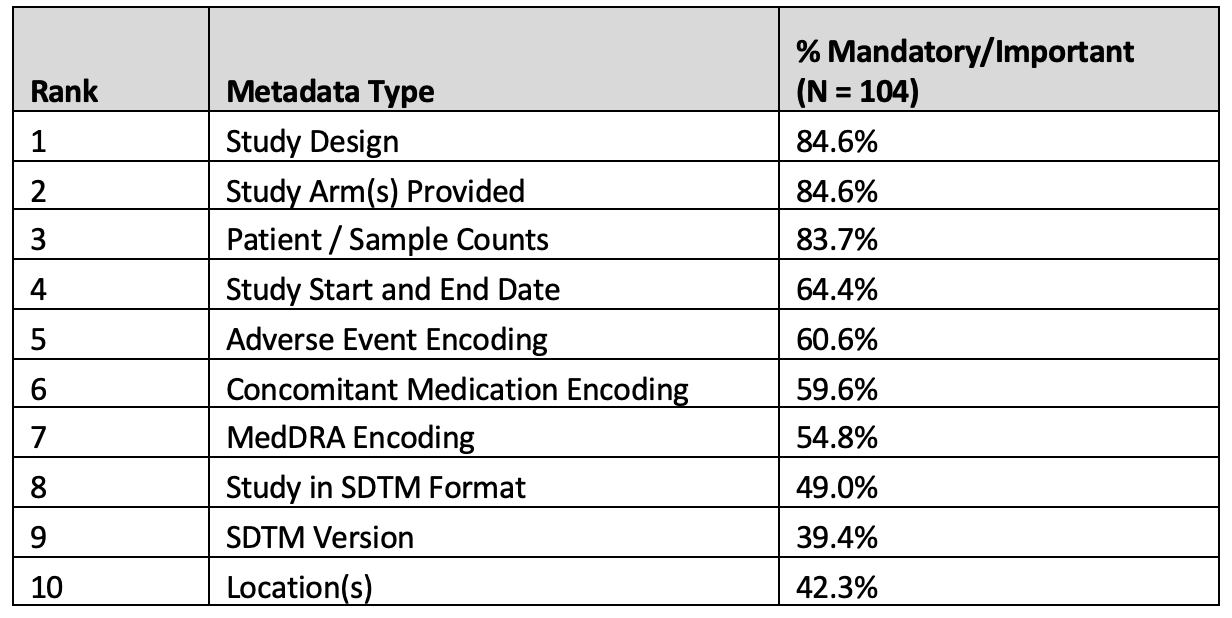

Respondents were also asked to evaluate the importance of having key metadata and study parameters prior to download or access. For analysis, responses to the type of metadata was grouped into three categories:

- Mandatory for use/important

- Useful

- Not relevant/ Not required

Their frequencies expressed in percentages were then computed for each type of metadata.

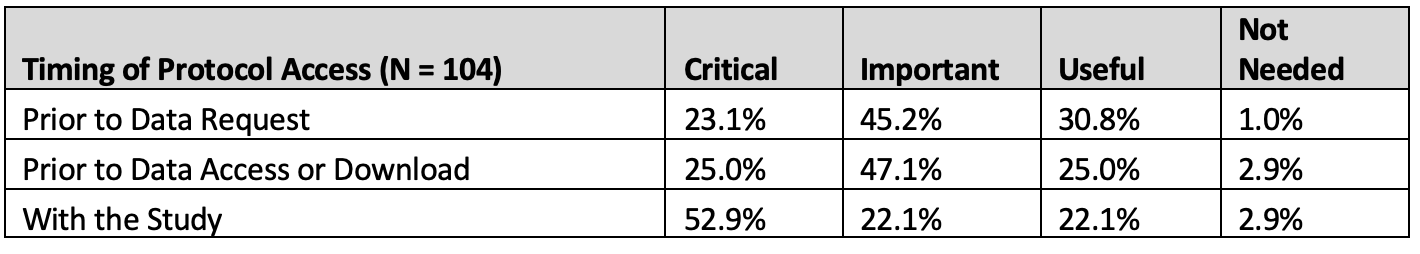

The timing of access to certain supporting documents and other relevant information can provide important context prior to data request, access, or download. Based on the author's experience, key documents or information that may assist in determining suitability for a study for a particular research question or need can include a redacted study protocol and information about key data redactions such as adverse events, demographics, and laboratory values.

For the purpose of this research, survey questions on the timing of access to these supporting documents included redacted study protocol, adverse events, demographics and laboratory values.

Response analysis of the timing of redacted study protocol access and relative importance was done by calculating the response frequencies for the different timings per the following categories: Critical, Important, Useful, and Not Needed.

Response Analysis of whether data redaction information was needed and, if so when data redaction information should be made available to the researcher was calculated for each redaction type.

The analysis results were summarized in tabular formats. All survey data, redacted for respondent privacy as noted above, is available in the supplemental tables referenced in Exhibit A.

Strengths and limitations

- The survey was developed by a diverse multi-stakeholder group of subject matter experts, including individuals with data contribution expertise, research use experience, and Data Sharing Platform governance responsibilities. The survey questions were further informed by collated data contribution information from multiple DSPs.16

- The results are an artifact of survey distribution, which was limited by the contacts and reach available to the authors. Therefore, the results may not reflect the full diversity of the clinical research ecosystem, and the respondent distribution may under-represent certain organization types. In particular, the authors are aware that there is a gap in small biopharma representation due to the relative size of the Clinical Research Data Sharing Alliance’s (CRDSA) biopharma member companies.

- Survey response rates varied by distribution source and organization type, which may serve to bias responses toward those most engaged in the data-sharing ecosystem. Therefore, one-time or limited-use researchers may be under-represented.

- The survey focused on some of the technical elements of data sharing (documents and datasets, timing of document provision, etc.). The authors recognize there are many non-technical aspects of the data sharing ecosystem that have a significant impact on the researcher experience. These include, but aren’t limited to, platform and data contributor access policies; intellectual property and competitive considerations; and data contribution resource investment.

Results

Demographics

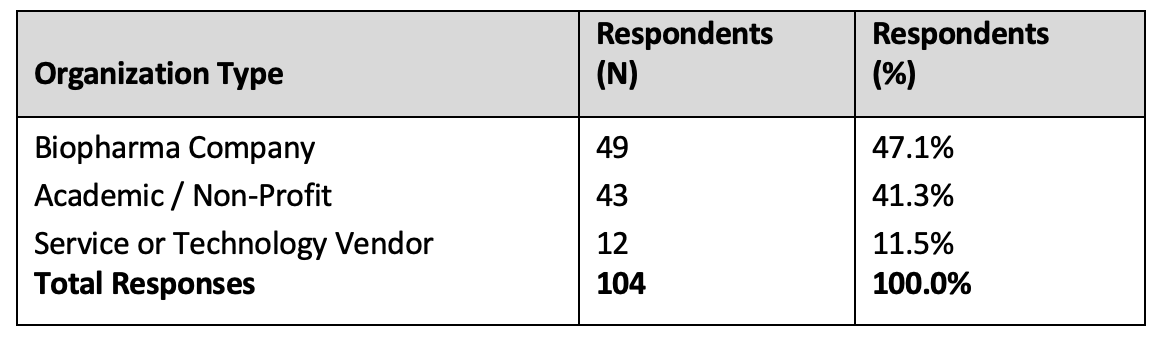

A total of 104 respondents completed the survey. Respondents were grouped by organization type and are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Respondents by organization type

The number of Service or Technology Vendor responses was too low to draw conclusions reliably representative of the category. In almost all cases, the Service or Technology Vendor responses were not meaningfully different from those provided by biopharma respondents. Therefore, the presentation of comparison results focuses on Academic/Non-Profit and biopharma responses, noting where Service/Technology responses differ from the biopharma responses. “All” is inclusive of total responses from the three categories, including Service or Technology Vendor responses.

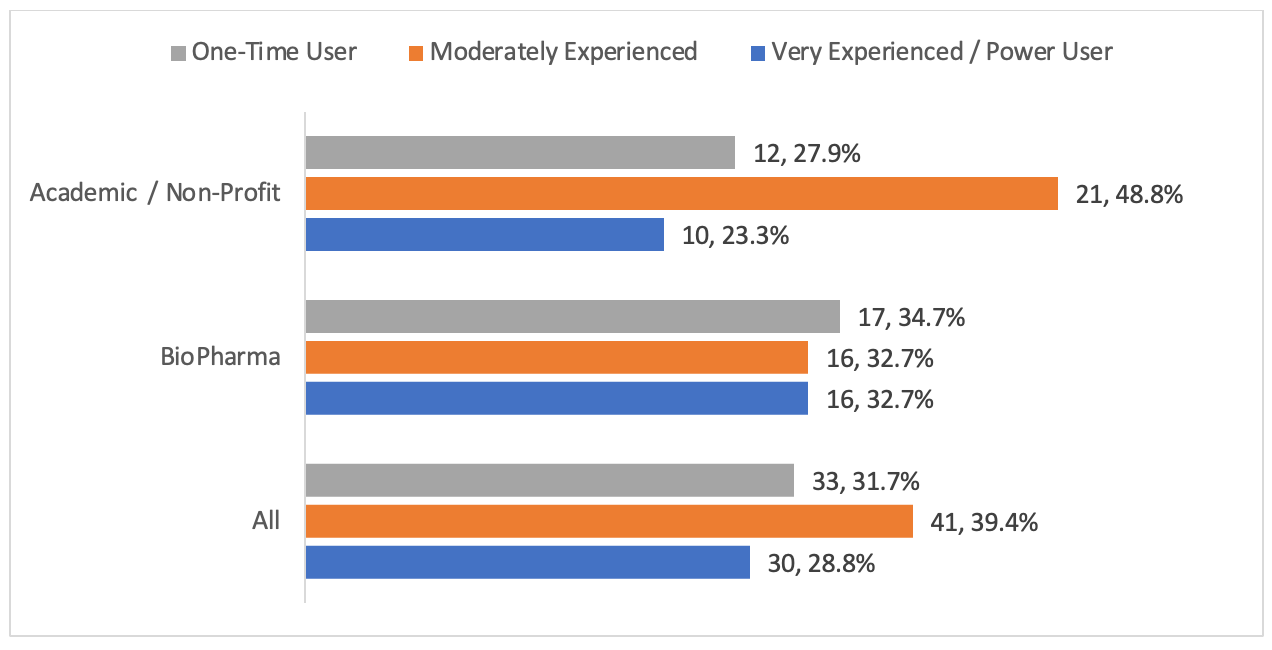

Figure 1. Respondents experience level

Biopharma experience levels were almost evenly distributed (Figure 1). Biopharma respondents were more likely to be in the Very Experienced/Power User Category (32.7%, n = 16 of 49) when compared to Academic / Non-Profit (23.3%, 10 of 43). Conversely, Academic respondents were more likely to be Moderately Experienced (48.8%, 21 of 43), with a lower percentage of One-Time Users (27.9%, 12 of 43) when compared to biopharma (34.7%, 17 of 49).

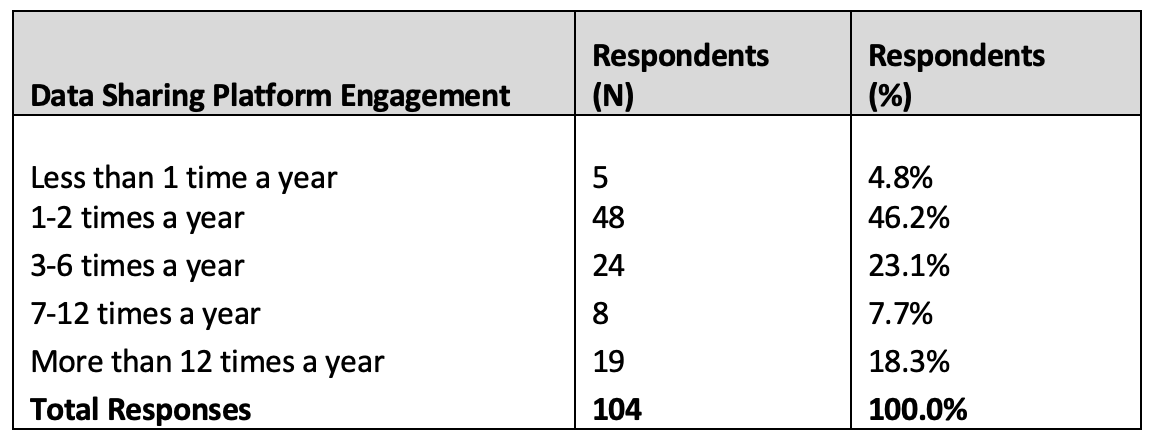

Table 2. Data sharing platform engagement frequency

95.2% of overall respondents (n = 99 of 104) engaged with data sharing platforms one or more times per year (Table 2). There were no meaningful frequency differences between organization types.

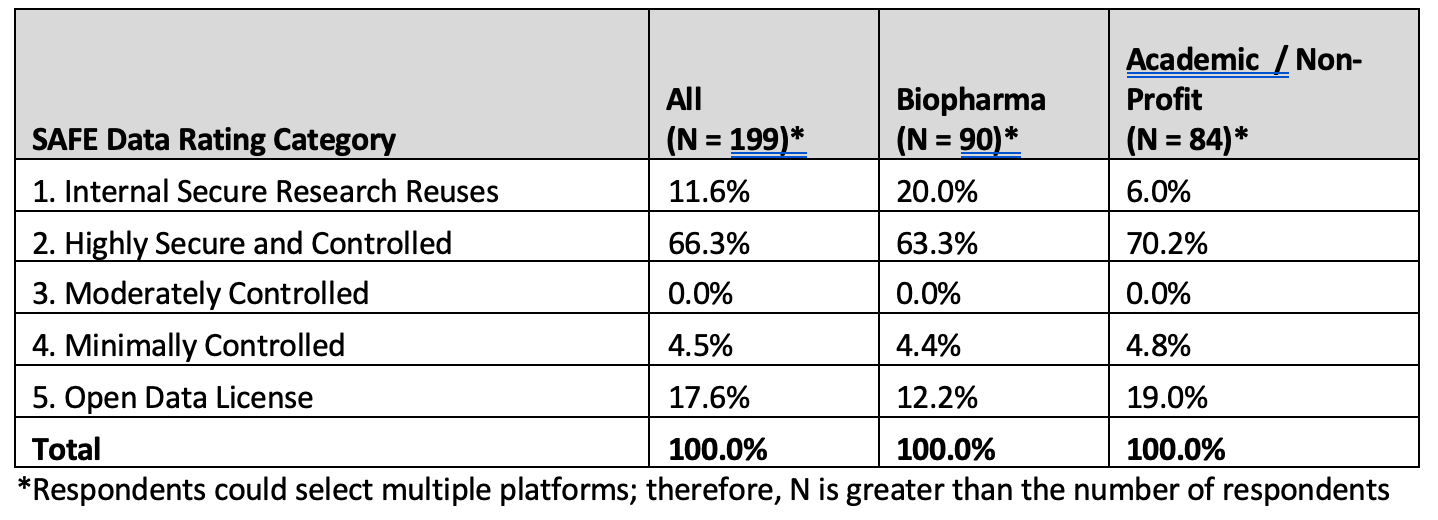

On platform usage, Respondents noted 10 unique DSPs, with an average of just under two platforms (1.93) per respondent. The responses were categorized by applying the SAFE data categories and are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. SAFE data platform categorization frequency

The Internal Secure Research Reuses category (1) includes data warehouses/data marts internal to organizations. External data sharing platforms are categorized as Highly Secure and Controlled, Moderately Controlled, Minimally Controlled, and Open Data License platforms. Compared to Academic / Non-Profit respondents, biopharma respondents are more likely to use internal data platforms (20% versus 6%, respectively). Service and Technology vendor responses (included in “All”) are not summarized separately in the table due to the limited number of respondents; however, those responses did diverge from both biopharma and Academic / Non-Profit, with 33% (4 of 12) of mentioned platforms in the Open Data License category (5).

Data requests / usage

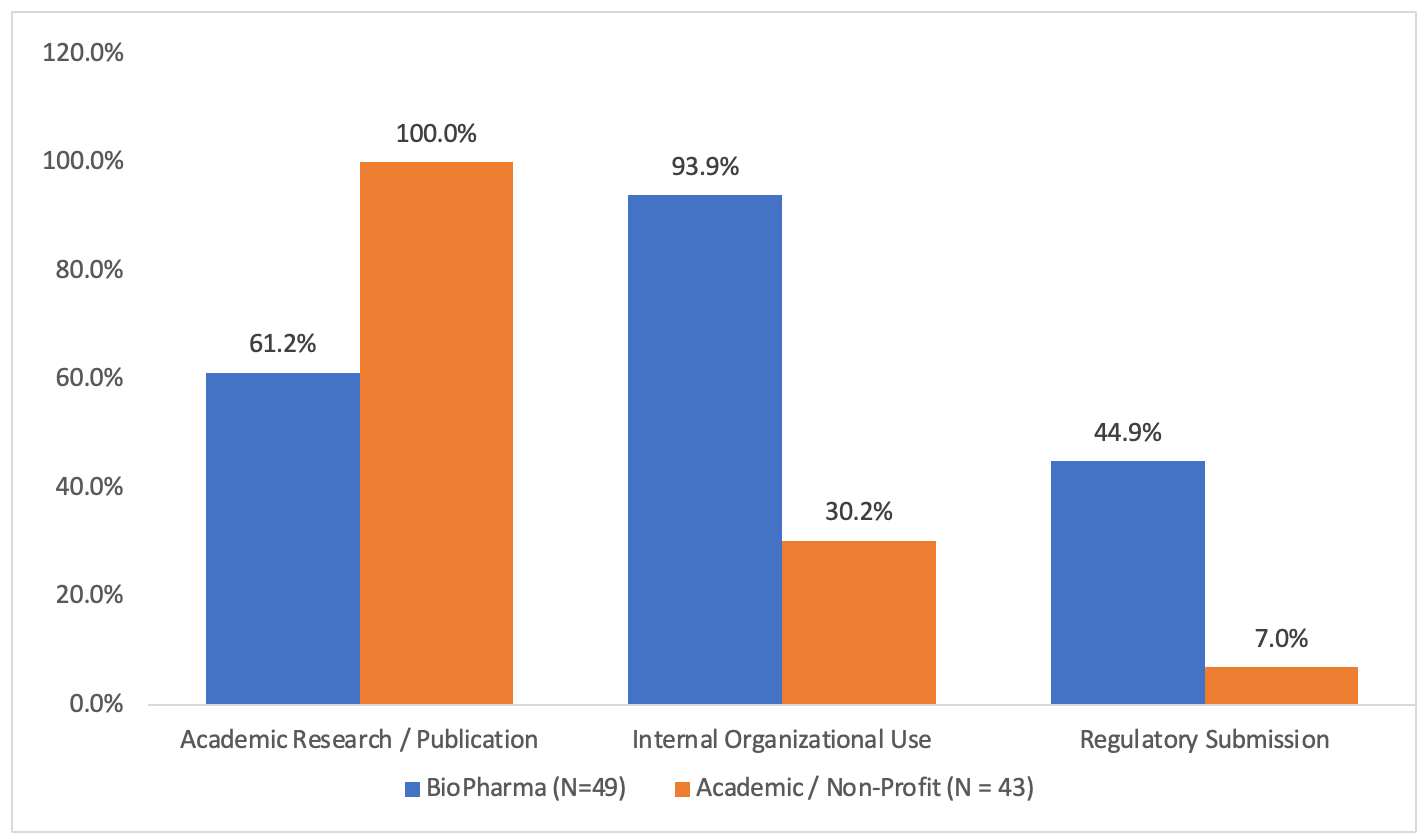

The results of respondents purpose (secondary use) of data request per organization type is shown in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2. Secondary data use case distribution

Service and Technology Vendor responses showed characteristics of both other categories, with a 92% response rate for Academic Research use (approaching Academic / Non-Profit response frequency) and a 42% Regulatory Submission response rate (similar to biopharma response frequency).

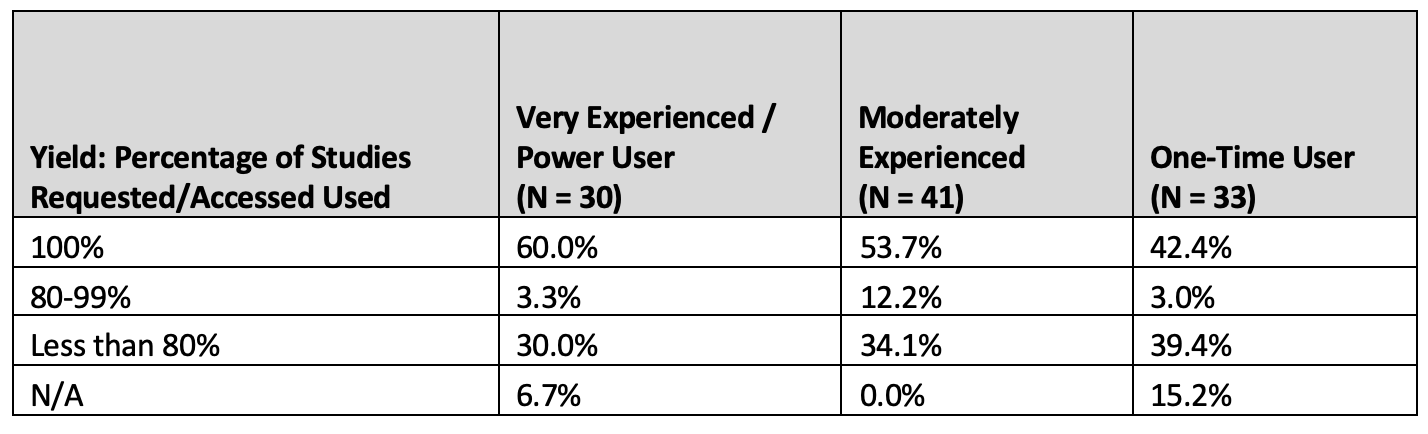

Results of respondents usage yield per experience level is presented in table 4 below.

Table 4. Study use yield by experience level

As the respondent experience level decreases, the usable study yield decreases, with 100% yield decreasing by 29.3% for One-Time Users compared to the most experienced respondent group.

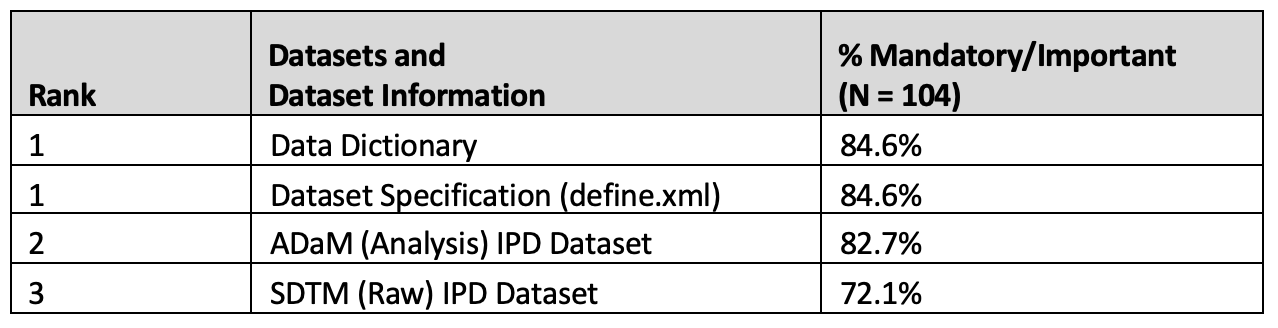

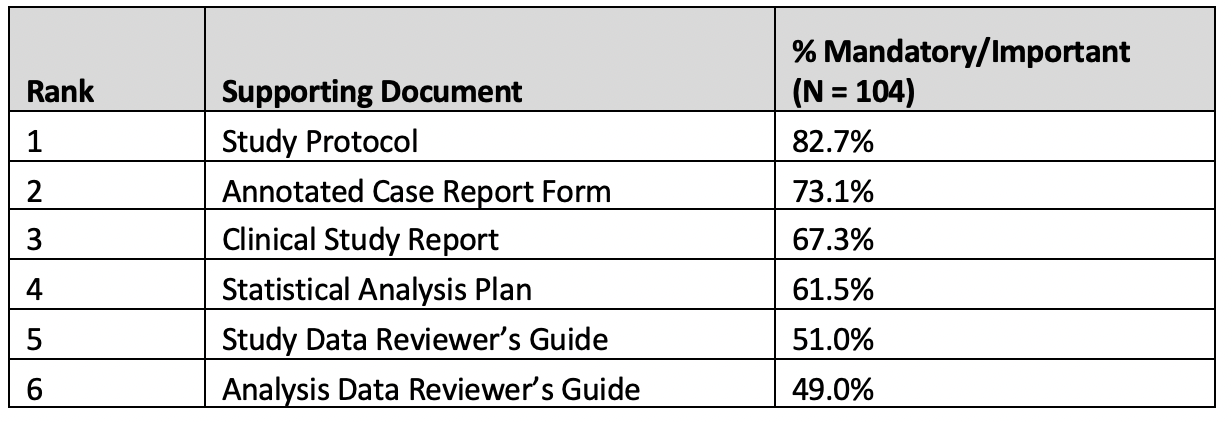

Datasets and supporting documentation

Results of responses were consistent across organization types and respondent experience levels and are considered as a pool group in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5. Datasets and dataset information

Table 6. Supporting documents

The results of responses on the importance variable-Level data transformation report were also consistent across organization type, and respondent experience levels and are considered as a pool group in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Importance of a variable-level data transformation report

Metadata collection

Results of the importance of key metadata required by researchers prior to access to study data are presented in Table 7 below:

Table 7. Metadata collection

Timing of provided information

Timely provision of supporting information and documentation can provide researchers with information to determine study suitability prior to data request, access, or download.

Results of when certain study supporting information and documentation as well as study data redaction information are required by researchers are shown in Table 8 and 9 respectively.

Table 8. Timing of protocol access

68.3% of all respondents evaluated redacted protocol access Prior to Data Request as Critical or Important, with 72.1% placing Critical or Important value on having access to the redacted protocol prior to study access or download.

The results of data redaction transparency timing for adverse events redactions, demographics redactions, and laboratory values redactions are needed are presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Data redaction transparency

A high proportion of respondents overall identify a need for redaction transparency. 89.4% for Adverse Events and 93.3% each for Demographics and Laboratory Values, with almost half (46%, 48%, and 49%, respectively) responding that the information is needed prior to accessing or downloading the study. There were no major respondent demographic differences in requiring the availability of the different data redactions at study access/download.

Discussion

The information from the survey results provides a snapshot of the current landscape of secondary use of clinical trial data through internal and external data sharing amongst the different organization types and use cases represented by the respondents.

Of the 104 respondents, the survey had a balanced sample of responses between biopharma companies and academic institutions/non-profit organizations (47% vs. 41%). Respondents were generally experienced users of one or more DSPs, with just over 68% indicating a moderate to power user experience level. This was supported by the frequency of DSP platform engagement, with over 95% of respondents engaging with DSPs one or more times a year. This level of experience and frequency of engagement may indicate that experienced users act as conduits to broader research teams within their organization. It's also notable that responses regarding the IPD data elements (datasets, documentation, and metadata) were consistent across organization types and experience levels. This shows that the survey responses are informed by direct experience and represent the needs of broader teams using secondary clinical trial data.

Across all organization types, almost 4 in 5 respondents indicated usage of DSPs categorized as Internal Secure Research Reuse and Highly Secure and Controlled. From a data contributor perspective, these two categories provide the most control over downstream access and use and are, therefore, generally considered the “safest” data sharing environments. Given the usage prevalence, it is reasonable to assume that respondents generally calibrated expectations to what would, or should, be available on these more restrictive platforms. Based on the author’s direct experience, it is also worth noting that some internal platforms may include both organization-specific secondary use data and datasets sourced from external DSPs.

The research objectives included understanding key factors of data utility and determining relative value to researchers of various types of IPD datasets, supporting documents, and metadata. It’s notable that responses regarding the importance of the various elements, as well as timing for researcher access, were consistent across all user types. While it is clear that certain documents or metadata are more universally useful (e.g. the Study Protocol), it’s important to remember that lower-ranking elements may be equally important for a specific research question or use. Also noteworthy is that when the Useful responses are included, the percentages rise to over 90% for almost all supporting documents and metadata elements.

An important piece of information that sometimes is underappreciated is an anonymization report describing the variable-level data transformations that took place. The survey results support the potential value of this report, with under 79% of respondents rating it’s value as 4 or 5, where 5 was Mandatory for Use. The survey results further support the importance of redaction transparency to researchers, with 89.4 to 93.3% of respondents indicating a need for Adverse Event, Demographics, and Laboratory Values redaction transparency.

While the survey responses are consistent, a 2022 CRDSA review of publicly available bipPharma data sharing policies13 found significant variability in the datasets and documentation sponsors make available to researchers. This suggests that community-wide agreement on provided supporting documentation and transformation information would be highly valuable for evaluating the potential utility of shared data.

The minority of respondents not seeing value in particular documents or supporting information may be an artifact of their specific research use but more likely highlights a knowledge gap that would benefit from community education. This highlights a need to educate the research community, particularly less experienced secondary data users, on the value and use of the various supporting documents and metadata elements.

When embarking on this research, the authors hypothesized that the timing of information availability is a critical consideration. The survey results support this hypothesis, indicating the importance of not only the provision of certain information, including the redacted study protocol and key redaction information but the criticality of access timing. One of the biggest challenges faced by researchers is ensuring that the data requested/accessed is fit for purpose for their specific research question or scientific problem. Over 97% of respondents indicated the importance of access to the study protocol prior to data request or data access/download. This suggests that providing key supporting documents and metadata earlier in the data access process can increase the likelihood that requested data will be used for its intended purpose and may lead to a significant increase in meaningful data reuse.

Conclusion

As we reflect on the survey results, it’s clear that to best serve the research community, there is a need for the data sharing ecosystem to establish and promulgate standards for the provision and timing of supporting documents and information provided as part of secondary data study contributions. Common standards for sharing data intended for secondary data usecan create process efficiency and information transparency that would benefit the research community and, equally important, benefit data contributors by ensuring their investment in data preparation time and resources will maximize research outcomes. Greater standardization in the information shared and made available through DSPs could accelerate the reuse of trial data, improving clinical trial development and enabling new innovative medicines to reach patients faster.

Ernest Odame, director, global evidence and outcomes, oncology, Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc; Tracy Burgess, director, PD data sciences, Genentech, a member of the Roche Group; Luk Arbuckle, chief methodologist, Privacy Analytics, an IQVIA company; Andrei Belcin, senior data analyst, Privacy Analytics, an IQVIA company; Gwenyth Jones, data science and statistics; University of Michigan; Peter Mesenbrink, executive director, biostatistics, Novartis; Ramona Walls, executive director of data science, Data Collaboration Center, Critical Path Institute; and Aaron Mann, CEO, Clinical Research Data Sharing Alliance

References

- Karpen, S. R., White, J. K., Mullin, A. P., O’Doherty, I., Hudson, L. D., Romero, K., Sivakumaran, S., Stephenson, D., Turner, E. C., & Larkindale, J. (2021). Effective Data Sharing as a Conduit for Advancing Medical Product Development. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 55(3), 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-020-00255-8

- Joint Statement on transparency and data integrity International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA) and WHO. (2021, May 7). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/07-05-2021-joint-statement-on-transparency-and-data-integrityinternational-coalition-of-medicines-regulatory-authorities-(icmra)-and-who

- Collins, F. S. (2020, October 29). Statement on Final NIH Policy for Data Management and Sharing. National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/statement-final-nih-policy-data-management-sharing

- G7 Research Compact. (2021, July 12). Gov.UK.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1001133/G7_2021_Research_Compact__PDF__356KB__2_pages_.pdf

- European Medicines Agency policy on publication of clinical data for medicinal products for human use. (2019). In ema.europa.eu (EMA/144064/2019). European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/european-medicines-agency-policy-publication-clinical-data-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf

- Mishra-Kalyani, P., Amiri Kordestani, L., Rivera, D., Singh, H., Ibrahim, A., DeClaro, R., Shen, Y., Tang, S., Sridhara, R., Kluetz, P., Concato, J., Pazdur, R., & Beaver, J. (2022). External control arms in oncology: current use and future directions. Annals of Oncology, 33(4), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.12.015

- Roberts, L., Arbuckle, L., Belcin, A., Burris, C., Gallagher, C., & Mann, A. (2022, September 12). A Review of BioPharma Sponsor Data Sharing Policies and Protection Methodologies [White Paper]. Clinical Research Data Sharing Alliance. https://crdsalliance.org/?smd_process_download=1&download_id=469

- Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., Blomberg, N., Boiten, J. W., da Silva Santos, L. B., Bourne, P. E., Bouwman, J., Brookes, A. J., Clark, T., Crosas, M., Dillo, I., Dumon, O., Edmunds, S., Evelo, C. T., Finkers, R., . . . Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

- Kuntz, R. E., Antman, E. M., Califf, R. M., Ingelfinger, J. R., Krumholz, H. M., Ommaya, A., Peterson, E. D., Ross, J. S., Waldstreicher, J., Wang, S. V., Zarin, D. A., Whicher, D. M., Siddiqi, S. M., & Hamilton Lopez, M. (2019). Individual Patient-Level Data Sharing for Continuous Learning: A Strategy for Trial Data Sharing. NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/201906b

- Rydzewska, L. H. M., Stewart, L. A., & Tierney, J. F. (2022). Sharing individual participant data: through a systematic reviewer lens. Trials, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05787-4

- Branson, J., Sundler, M., & Tucker, K. (n.d.). Secondary use of data - Unleashing Data Assets to Create Value. In PSI Data Transparency SIG. https://www.emwa.org/media/4058/spin2021datatransp.pdf

- Committee on Strategies for Responsible Sharing of Clinical Trial Data, Board on Health Sciences Policy, & Institute of Medicine. (2015). Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 31–46. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/18998/sharing-clinical-trial-data-maximizing-benefits-minimizing-risk

- Roberts, L., Arbuckle, L., Belcin, A., Burris, C., Gallagher, C., & Mann, A. (2022, September 12). A Review of BioPharma Sponsor Data Sharing Policies and Protection Methodologies [White Paper]. Clinical Research Data Sharing Alliance. https://crdsalliance.org/?smd_process_download=1&download_id=469

- Looker Studio Overview. (n.d.). https://lookerstudio.google.com/overview

- Bamford, S., Lyons, S., Arbuckle, L., & Chetelat, P. (2022a). Sharing Anonymized and Functionally Effective (SAFE) Data Standard for Safely Sharing Rich Clinical Trial Data. Applied Clinical Trials, 31(7/8). https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/sharing-anonymized-and-functionally-effective-safe-data-standard-for-safely-sharing-rich-clinical-trial-data

Appendix A: Data Sharing Platforms

- BioLINCC (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/)

- Clinical Study Data Request (CSDR) (https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/)

- Critical Path Institute (C-Path) (https://c-path.org/)

- DataCelerate (https://www.transceleratebiopharmainc.com/initiatives/datacelerate/)

- Internal Data Mart(s) (no reference)

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) Data Sharing Platforms (https://datascience.cancer.gov/data-sharing)

- Project Data Sphere (https://www.projectdatasphere.org/)

- Vivli (https://vivli.org/)

- The Yale Open Data Access Project (The YODA Project) (https://yoda.yale.edu/)

EXHIBIT B:

1. Sample Survey 2. Survey Results Data Table (clicking this link will download the Excel file to your computer)Unifying Industry to Better Understand GCP Guidance

May 7th 2025In this episode of the Applied Clinical Trials Podcast, David Nickerson, head of clinical quality management at EMD Serono; and Arlene Lee, director of product management, data quality & risk management solutions at Medidata, discuss the newest ICH E6(R3) GCP guidelines as well as how TransCelerate and ACRO have partnered to help stakeholders better acclimate to these guidelines.

Beyond the Molecule: How Human-Centered Design Unlocks AI's Promise in Pharma

June 23rd 2025How human-centered AI that is focused on customer, user, and employee experience can drive real transformation in clinical trials and beyond by aligning intelligent technologies with the people who use them.